As NASA’s Voyager 1 Surveys Interstellar Space, Its Density Measurements Are Making Waves

Until recently, every spacecraft in history had made all of its measurements inside our heliosphere, the magnetic bubble inflated by our Sun. But on August 25, 2012, NASA’s Voyager 1 changed that. As it crossed the heliosphere’s boundary, it became the first human-made object to enter – and measure – interstellar space. Now eight years into its interstellar journey, Voyager 1’s data is yielding new insights into what that frontier is like.

If our heliosphere is a ship sailing interstellar waters, Voyager 1 is a life raft just dropped from the deck, determined to survey the currents. For now, any rough waters it feels are mostly from our heliosphere’s wake. But farther out, it will sense the stirrings from sources deeper in the cosmos. Eventually, our heliosphere’s presence will fade from its measurements completely.

“We have some ideas about how far Voyager will need to get to start seeing more pure interstellar waters, so to speak,” said Stella Ocker, a Ph.D. student at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, and the newest member of the Voyager team. “But we're not entirely sure when we'll reach that point.”

Ocker’s new study, published on Monday in Nature Astronomy, reports what may be the first continuous measurement of the density of material in interstellar space. “This detection offers us a new way to measure the density of interstellar space and opens up a new pathway for us to explore the structure of the very nearby interstellar medium,” Ocker said.

When one pictures the stuff between the stars – astronomers call it the “interstellar medium,” a spread-out soup of particles and radiation – one might imagine a calm, silent, serene environment. That would be a mistake.

“I have used the phrase ‘the quiescent interstellar medium’ – but you can find lots of places that are not particularly quiescent,” said Jim Cordes, space physicist at Cornell and co-author of the paper.

Like the ocean, the interstellar medium is full of turbulent waves. The largest come from our galaxy’s rotation, as space smears against itself and sets forth undulations tens of light-years across. Smaller (though still gigantic) waves rush from supernova blasts, stretching billions of miles from crest to crest. The smallest ripples are usually from our own Sun, as solar eruptions send shockwaves through space that permeate our heliosphere’s lining.

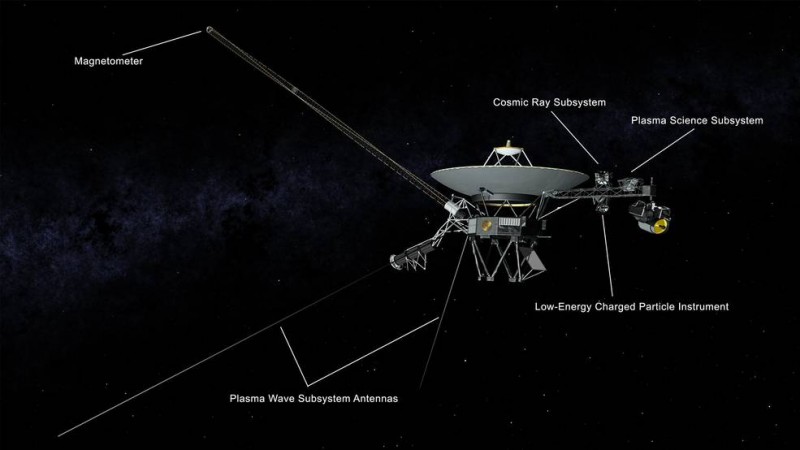

These crashing waves reveal clues about the density of the interstellar medium – a value that affects our understanding of the shape of our heliosphere, how stars form, and even our own location in the galaxy. As these waves reverberate through space, they vibrate the electrons around them, which ring out at characteristic frequencies depending on how crammed together they are. The higher the pitch of that ringing, the higher the electron density. Voyager 1’s Plasma Wave Subsystem – which includes two “bunny ear” antennas sticking out 30 feet (10 meters) behind the spacecraft – was designed to hear that ringing.

Illustration of NASA's Voyager spacecraft showing the antennas used by the Plasma Wave Subsystem and other instruments.Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

In November 2012, three months after exiting the heliosphere, Voyager 1 heard interstellar sounds for the first time. Six months later, another “whistle” appeared – this time louder and even higher pitched. The interstellar medium appeared to be getting thicker, and quickly.

These momentary whistles continue at irregular intervals in Voyager’s data today. They’re an excellent way to study the interstellar medium’s density, but it does take some patience.

“They've only been seen about once a year, so relying on these kind of fortuitous events meant that our map of the density of interstellar space was kind of sparse,” Ocker said.

Ocker set out to find a running measure of interstellar medium density to fill in the gaps – one that doesn’t depend on the occasional shockwaves propagating out from the Sun. After filtering through Voyager 1’s data, looking for weak but consistent signals, she found a promising candidate. It started to pick up in mid-2017, right around the time of another whistle.

“It’s virtually a single tone,” said Ocker. “And over time, we do see it change – but the way the frequency moves around tells us how the density is changing.”

Ocker calls the new signal a plasma wave emission, and it, too, appeared to track the density of interstellar space. When the abrupt whistles appeared in the data, the tone of the emission rises and falls with them. The signal also resembles one observed in Earth’s upper atmosphere that’s known to track with the electron density there.

“This is really exciting, because we are able to regularly sample the density over a very long stretch of space, the longest stretch of space that we have so far,” said Ocker. “This provides us with the most complete map of the density and the interstellar medium as seen by Voyager.”

Based on the signal, electron density around Voyager 1 started rising in 2013 and reached its current levels about mid-2015, a roughly 40-fold increase in density. The spacecraft appears to be in a similar density range, with some fluctuations, through the entire dataset they analyzed which ended in early 2020.

Ocker and her colleagues are currently trying to develop a physical model of how the plasma wave emission is produced that will be key to interpreting it. In the meantime, Voyager 1’s Plasma Wave Subsystem keeps sending back data farther and farther from home, where every new discovery has the potential to make us reimagine our home in the cosmos.

Source: nasa.gov