The first-ever photo of a black hole was released on Wednesday, giving a physical form to an astronomical phenomenon that had previously only been hypothesized. Imaging a black hole for the first time was a major accomplishment — and an emotionally moving one for the scientists involved — but perhaps the most important part of this discovery isn’t what it revealed but what it confirmed.

In a series of six papers published Wednesday in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, over 200 scientists involved in the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration describe how they collected enough light from the black hole at the center of the galaxy Messier 87 to reveal humanity’s first look at a black hole.

The image of the black hole is just one artifact of this immense project. Through the image, astronomers got their first close-up glimpse at an astronomical phenomenon whose existence was predicted a century ago, allowing them to test their previous theories against a new set of concrete data. The results, described below, could open up a new era of astrophysics.

It Fit the Predictions Perfectly

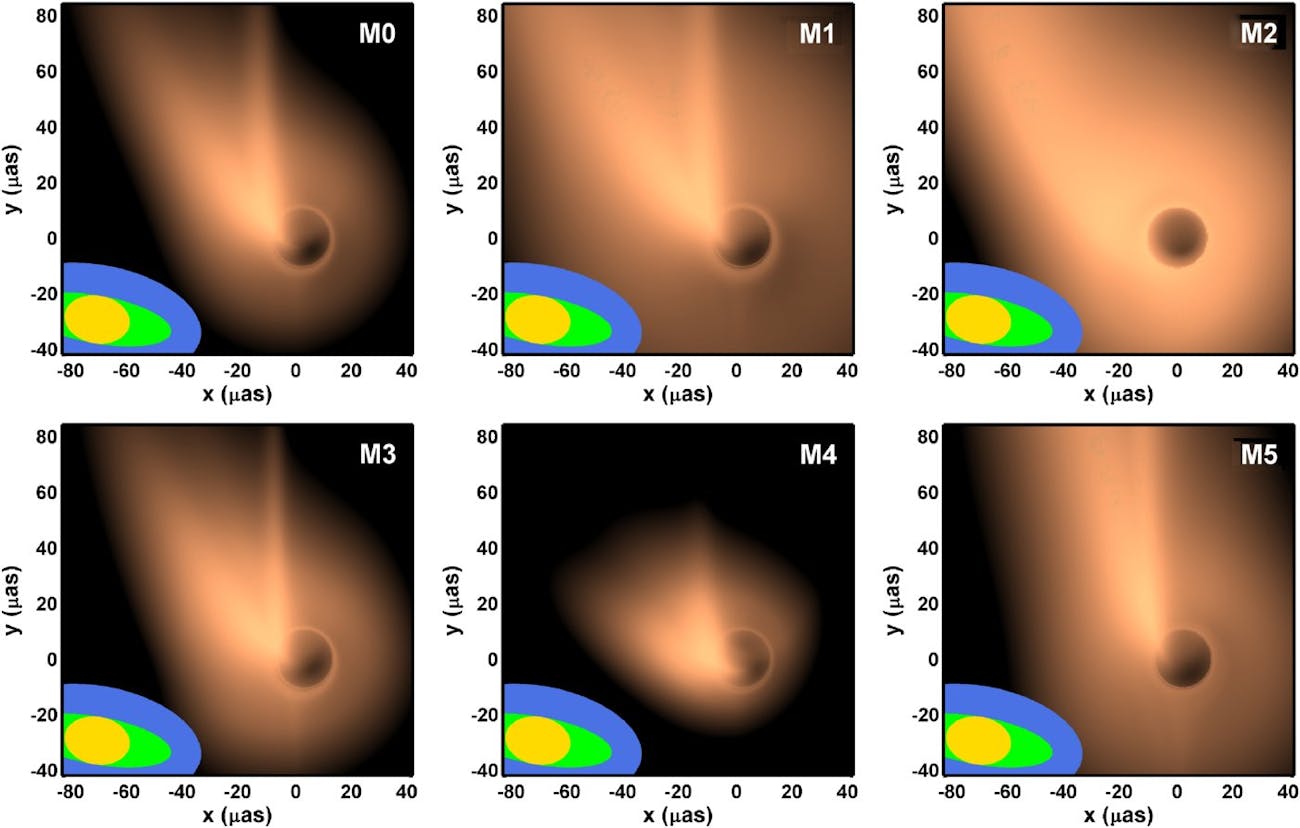

The image at the top of this article was created before scientists ever saw the M87 black hole, using mathematical predictions of how the black hole might look. The new image looks like a blurry version of the prediction, but as far as scientists are concerned, they might as well be the same.

“As far as I’m concerned, the most surprising thing about this image is that it’s not very surprising,” Avi Loeb, Ph.D., the founding director of Harvard’s Black Hole Initiative, tells Inverse. A decade ago, Loeb, who was not involved in capturing the M87 image, helped devise a prediction of what the M87 black hole might look like. On that project, he worked with Avery Broderick, Ph.D., an associate professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Waterloo who was involved with the M87 photograph.

“It looks very similar to the predictions that we have made,” says Loeb. “In a way, it’s reassuring and it’s gratifying to see that what we expected is indeed there.”

Here’s what Loeb and Broderick’s models looked like.

This Is the First Direct Test of Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity

Chi-Kwan Chan, Ph.D., a computational astrophysicist at the University of Arizona who was part of the M87 imaging project, tells Inverse that the new observations represent yet another piece of evidence that Einstein was right, a full century before humans had any way of seeing black holes.

Einstein’s theory of general relativity predicted that gravity is a result of massive objects changing the curvature of space time. Back in 1916, Einstein predicted that black holes — like the M87 black hole, which is around 6.5 billion times the mass of our sun — would have a huge influence on the objects around them, and the new observations bear this out.

“Until today, Einstein’s theory has been tested many, many times, but all of them are in the weak field regime,” Chan says. “We have not had a direct test of general relativity via a strong gravity object, a black hole. So I would say this is probably the first direct evidence that Einstein’s right again, via such a strong gravity object,” he adds.

“Scientifically, I think this is the most exciting thing.”

As far as the predictions being correct, Chan agrees with Loeb.

“Avi and I are in agreement that this is surprisingly unsurprising. We have a group at the University of Arizona that has done numerical simulations for a long time, and we have seen this simulated black hole image for a long time,” he says.

But if you flip it, he points out, this is further evidence that Einstein was right again. After all, these simulations are based on Einstein’s theories.

“The fact that the observations and the simulations are consistent — I think that’s amazing,” says Chan.

Astronomers Can Correctly Estimate the Mass of Black Holes

Before astronomers observed the black hole at the center of Messier 87, they could only indirectly measure the mass of black holes. This was done by observing how quickly stars rotate around it since the black hole at the center of each galaxy was theoretically the thing influencing the gravity of all the other objects around it. But now that scientists can just snap a picture — even if that “snap” includes five petabytes of data — the task has gotten much simpler. Plus, it turns out that, once again, the predictions were pretty much right.

“Before the Event Horizon Telescope experiment, people were trying to estimate the mass of this supermassive black hole,” says Chan. “But this time we can put a ruler on top of the picture … It’s quite cool that we can do something that was not possible before from the image.”

And while it might not sound very exciting that this observation simply confirmed previous hypotheses about black holes, it’s a pretty big deal that Earth-based astronomers and physicists have been right about them for years without ever being able to see them.

“We’ve been studying black holes for so long, that it’s easy to forget that none of us has ever seen one,” France Córdova, director of the National Science Foundation, told reporters on Wednesday.

Perhaps most importantly, this latest observation signals the beginning of a new phase of astrophysics, in which scientists can use new types of direct signals from black holes rather than relying on secondhand observations.

“We live in an exciting time,” says Loeb. “The study of black holes is entering the experimental phase, where we can probe the immediate vicinity of these systems.”