Atmospheric scientists may pray for a global dust storm to blow up on Mars, but the rest of us . . . please, no! Just as the Red Planet began to inch into the evening sky, a swath of bright, yellow dust clouds lit up over the dark albedo feature Mare Acidalium at the end of May.

Within days, the gale had moved south and expanded, covering much of Sinus Meridiani, Oxia Palus, and Margaritifer Sinus and coursing the length and breadth of the sprawling Martian canyon system Valles Marineris. This is a big storm. Under the eye of NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, it measures more than 18 million square km (7 million square miles), an area greater than the continent of North America. (But see update at the end of the article.)

While there's no way to foretell if the gale will balloon into a planet-girdling storm, NASA's Opportunity rover team has taken precautions to protect the rolling robot, which sits squarely in the storm's path in Sinus Meridiani. Science operations have been suspended to conserve power.

"A dark, perpetual night has settled over the rover's location in Mars' Perseverance Valley," reads the most recent agency press release, referring to thick clouds blowing dust in the area.

Looks wicked out there. This global map of Mars shows the growing dust storm as of June 6, 2018. The map was produced by the Mars Color Imager (MARCI) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSS

Opportunity made it through the last bad storm in 2007, but this one’s worse. Dust blocks the sunlight used by the rover's solar panels to create the power needed to run its instruments and stay warm. Mars is no picnic. Although dust storms can limit temperature extremes — analogous to a cloudy day on Earth — the longer they last, the less power available to the rover. Batteries only last so long.

This map of the planet Mars is based on observations made by amateur astronomers. The most prominent dark features for 4-inch or larger instruments are Syrtis Major, Mare Acidalium, Mare Erythraeum, and Mare Cimmerium. The storm began in Mare Acidalium (lower left) and tracked west across Chryse and Oxia Palus, then into Sinus Meridiani.

ALPO

Another perspective of the storm taken by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Malin Space Science Systems

The good news is that NASA engineers received a transmission from Opportunity on Sunday morning, a welcome sign that despite the worsening storm, the rover still has enough battery power to communicate with ground controllers. Meanwhile, the Mars Curiosity rover is still in the clear in the opposite hemisphere, though an increase in dust is expected in the coming days.

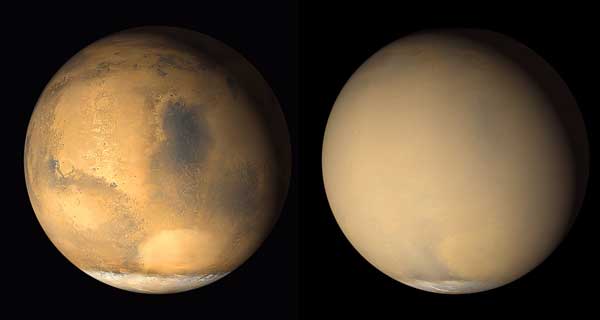

Two mages taken by NASA's Mars Global Surveyor orbiter in 2001 show the dramatic change in the planet's appearance before and during a global dust storm. North is up.

NASA / JPL / MSSS

The current storm is significantly larger than the 2005 storm but so far pales in comparison to the global storm that wracked the Red Planet in 2001. That one began in the bright, circular feature Hellas, an ancient impact basin with a floor 9 km deep in the planet's southern hemisphere. The ~10° temperature difference between basin bottom and surface drove winds that spawned a modest storm. But on June 27th that year, the storm exploded in size, spilling out of the basin to eventually cover the entire planet.

No one's certain on exactly how a big storm gets rolling, but it appears that a positive feedback loop can turn a zephyr into a monster under the right conditions:

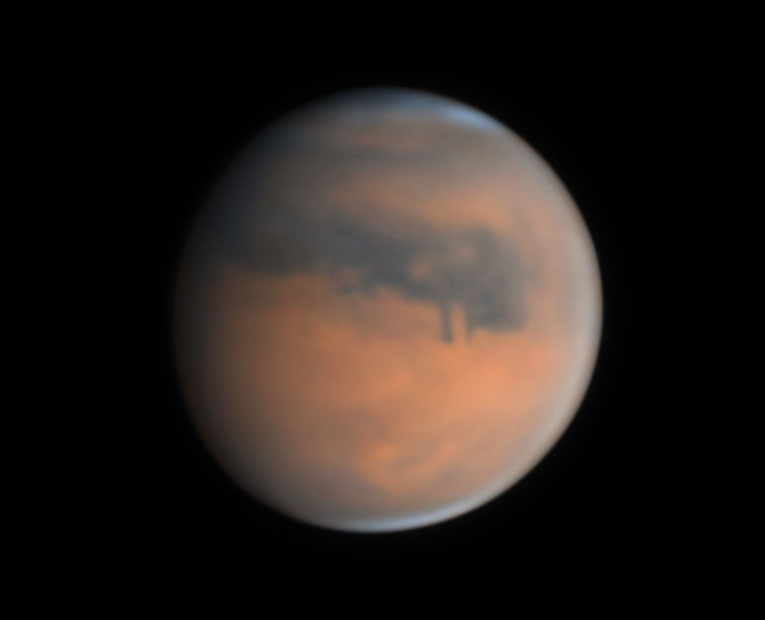

Before and after photos show significant changes wrought by the current storm. Dust now covers many of the dark surface markings visible earlier in May. The orange, linear feature near the center of Mars is the giant canyon system Valles Marineris — dark in May but now filled with bright dust!

Damien Peach (left) / Anthony Wesley

"One theory holds that airborne dust particles absorb sunlight and warm the Martian atmosphere in their vicinity," said Phil Christensen, planetary geologist at the University of Arizona, referring to the 2001 storm. "Warm pockets of air rush toward colder regions and generate winds. Strong winds lift more dust off the ground, which further heats the atmosphere." More heat means more energy and stronger winds, which lift even more dust into the air, amplifying a small disturbance into a large one.

This sequence of photos shows the development of the bright dust storm on Mars. It’s most obvious in the top row images. North is up.

Paul Maxson

This storm is a little different. Instead of occurring at the height of southern summer as in 2001 and 2005, it erupted in the northern hemisphere only days after the northern fall equinox. Similar to how arctic fronts descend one after another on North America during late fall and winter, multiple storm fronts parade along the north polar cap during Martian fall. Some of these can break off and head south, where they feast on warmer air and burgeon into much bigger storms.

Mars, now brighter than Sirius and a distinctive fiery hue, climbs above the tree line in the southeastern sky on June 10th. The planet rises late — around midnight local time in mid-June — and is best observed in early dawn when it stands due south on the meridian.

Bob King

From an observer's point of view, let's hope the dust settles ... literally. Mars is finally coming into its own. At magnitude –1.6, it's now brighter than any star in the night sky. On Monday morning (June 11th) I easily found it in my 8×50 finderscope at sunrise and did all my observing in a blue sky. Mars's apparent diameter has swelled to nearly 18″ (arcseconds) on its way to a chunky 24.3″ when it reaches opposition on July 27th. Closest approach to the Earth occurs on July 31st at 57.6 million kilometers, its most neighborly position since the 2003 opposition.

This more detailed map created by Damian Peach is based on photographs taken during the 2005 apparition. Changes, some subtle some not, occur in the tone and shape of some dark markings due to winds that alternately cover and uncover the landscape with dust. Click for a large version.

Damian Peach

Provided the storm takes a chill pill, telescopic observers have lots to see now through fall. First off, the south polar cap is obvious, and we'll be able to watch it shrink as its dry-ice shell sublimes in the intensifying spring heat. Large, dark albedo features like Syrtis Major, Hellas, Mare Tyhrrhenum, Mare Cimmerium, Solis Lacus (the Eye of Mars), Aurorae Sinus, Sinus Meridiani, and Sinus Sabaeus can be discerned in good seeing and with practice. A red filter and magnifications of 150× and higher will help to bring out them out.

Maryland amateur Robert Bunge sketched a wealth of detail on Mars as seen through his 6-inch telescope on June 5th. The thumb-shaped feature at left is Syrtis Major. The dotted bright area at right corresponds to the dust storm.

Robert Bunge

Observers in mid-northern latitudes will have to work harder than more southerly skywatchers to get their Mars fix. The planet spends much of the summer and fall in southern Capricornus, south of declination –20°. The seeing at that elevation is rarely good, the reason I recommend observing Mars near the meridian and as often as possible, the better to catch it on those rare nights of serene seeing and fine definition.

Be aware that even if we make it past the current storm, we're not out of the woods. Summer's a comin' for the south. As carbon dioxide ice vaporizes from the southern pole cap, expect new winds to develop and a good possibility for major storms to return in August and September. If you routinely observe Mars, a dust storm will betray itself by color (yellow-orange), brightness and the plain fact that a feature you saw a few nights has seemingly disappeared. I've watched them evolve night to night — most exciting!

Resources to enhance your Mars experience:

- Mars Profiler: find out which side of Mars and what features are visible

- 2018 Mars Gallery: the latest photos from amateurs around the world

- ALPO 2018 Perihelic Opposition Guide to Mars

- Mars weekly weather: reports based on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter imagery

*** Dust storm update June 13, 2018:

This series of images shows simulated views of a darkening Martian sky blotting out the Sun from the point of view of NASA’s Opportunity rover, with the right side simulating Opportunity’s current view in the global dust storm (June 2018). The left starts with a blindingly bright mid-afternoon sky, with the Sun appearing bigger because of brightness. The right shows the Sun so obscured by dust it looks like a pinprick.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / TAMU

NASA engineers attempted to contact the Opportunity rover on June 12 but did not hear back probably because the charge in its batteries has dropped below 24 volts. At that point, the rover enters low power mode where everything is turned off except the mission clock. The clock is programmed to wake the computer so it can check power levels. If there's not enough, the rover goes back to sleep until the next check.

The dust cover is now extreme at Opportunity's location and has spread to cover a quarter of the planet — equal to the combined area of North America and Russia. Mission engineers believe there may not be enough sunlight to charge the batteries for the next few days. The concern is that without battery power, the rover won't be able to keep its electronics alive. To hear the replay of the NASA teleconference about Opportunity's fate held earlier today, click here.

If there's a silver lining in this dark scenario, the increase in atmospheric temperature caused by the Sun-warmed dust along with the warming of the air with the arrival of spring will combine to moderate temperatures at Opportunity's location, keeping the rover just warm enough to survive till the dust clears.

*** Dust storm update June 14, 2018:

This set of images from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) shows the evolution of the dust storm (salmon-colored area) from May 31st, when the dust event was first detected, through June 11th. Rovers on the surface are indicated as icons.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

*** Dust storm update June 19, 2018:

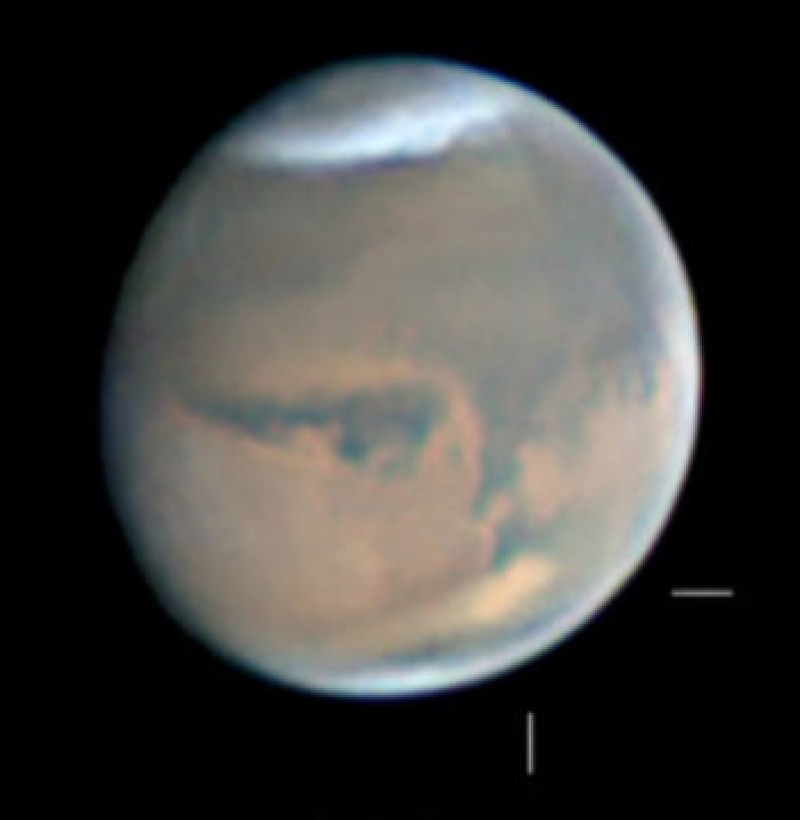

Only a few dark albedo markings still showed well on Mars when this photo was taken on June 15th at 7:49 UT. You're looking at the dark marking called Mare Cimmerium with Mare Chronium above it. Hints of Mare Tyrrhennum are seen under haze at far right. South is up.

Damian Peach / Chilescope Team

Conditions at Mars continue to worsen however the storm has not reached global proportions. For the moment, it still remains a large regional storm. Dust obscures many once prominent features including Syrtis Major, Sinus Meridiani and much of the south polar cap. The Opportunity rover is still silent and will likely remain so until the storm blows over.

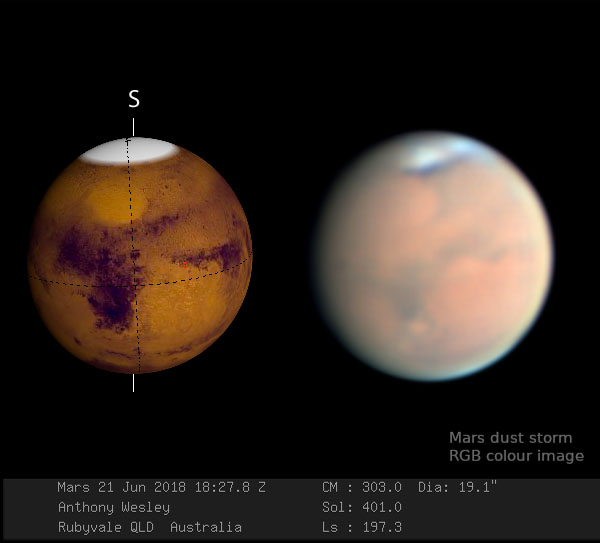

Australian amateur Anthony Wesley photographed Mars on June 19th and included a reference image made using WINJUPOSto show how much dust has altered the planet's appearance. The normally prominent feature Syrtis Major is heavily obscured as is much of the south polar cap.

*** Dust storm update June 22, 2018:

Recent photos taken by Australian amateur Anthony Wesley indicate that the dust may be starting to clear. His image from June 21 still shows plenty of suspended dust, but the dark albedo features Syrtis Major and Sinus Meridiani are beginning to show through the haze. There's also a prominent dark collar along the northern border of the south polar cap around CM 330°.

Some of Mars's better-known features are beginning to show through the dust in this photo taken on June 21.8 UT. The prominent dark "thumb" is Syrtis Major.

Anthony Wesley

I finally got a good view of Mars on June 21.4 UT (CM = 171°) through a 10-inch telescope and saw part of Mare Sirenum and Mare Cimmerium, which were crossing the central meridian at the time. The polar cap, which would normally be distinct, appeared pale-white and patchy using a magnification of 254x. You could see it was there but the outline was unclear. There's plenty of time for potentially great views with opposition still more than a month away.

Two images from the NASA's Curiosity rover depict the change in the color of light illuminating the Martian surface since the dust storm engulfed Gale Crater. The left image shows the "Duluth" drill site on May 21st; the right image is from June 17th. The cherry-red color in the post-storm photo is due to a couple of factors: The exposure time for the right image is nine times longer than the one on the left because of low-lighting conditions brought on by the dust. But the primary reason for the color change is the dust filters out most of the green and all of the blue light from the Sun.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSS

NASA attempts to contact the Opportunity rover every day, but there's still no reply. Meanwhile, the Curiosity rover on the other hemisphere of Mars has been recording thickening dust conditions. In other news, the storm is officially a "planet-encircling" or global dust event, according to Bruce Cantor of Malin Space Science Systems, San Diego, who is deputy principal investigator of the Mars Color Imager camera on board NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. This storm's more patchy compared to the big global storms of 1971-72 and 2001 which totally obscured the surface.

A self-portrait taken by NASA's Curiosity rover taken on Sol 2082 (June 15, 2018) at the "Duluth" drilling site. (center). A Martian dust storm has reduced sunlight and visibility at the rover's location.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSS

*** Dust storm update June 25, 2018:

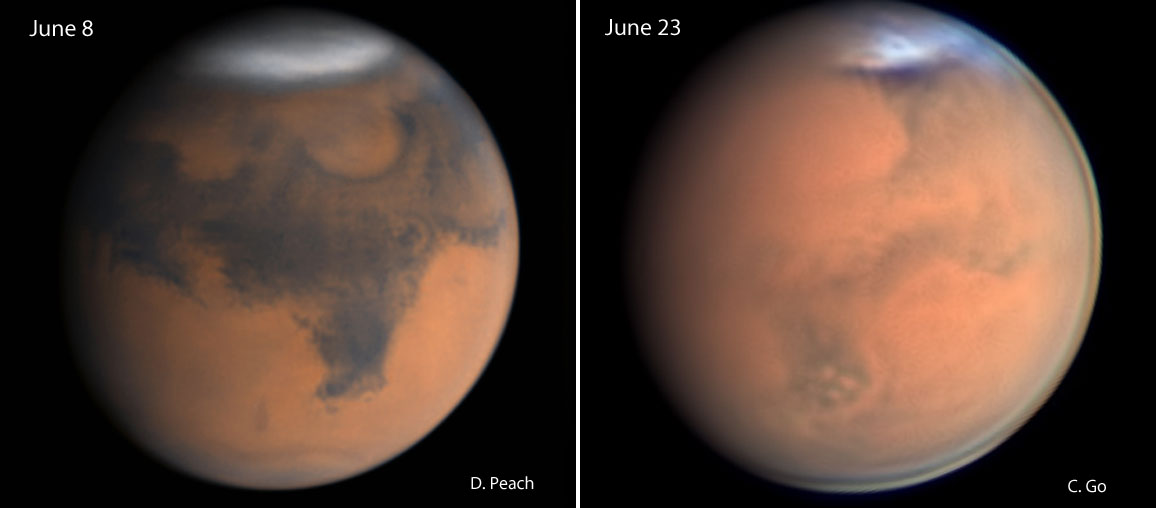

Ah, the good old days. These photos were taken 15 days apart and show the same hemisphere of Mars. Note how airborne dust has obscured the outlines of familiar features including Syrtis Major (dark India-shaped marking below center.) Dust also shrouds much of the south polar cap. CM = 300° on right image. South is up.

Damian Peach (left) / Christopher Go (right)

Mars remains hazy and most of the planet's dark markings show low contrast. But with patience and good seeing, observers are gradually making out a few more features. Syrtis Major and Sinus Meridiani are returning, but it appears that Mare Cimmerium has recently gone missing!

Mare Cimmerium is only visible as low contrast patches in this photo taken on June 24th. CM =238°. South is up.

Christoper Go

You can really see how dramatically the storm has altered the appearance of once prominent markings in the side-by-side panel above taken only two weeks apart. No word yet from the Opportunity rover — last contact was June 10th.

Why does Mars have planet-wide dust storms and not Earth? There are at least two factors involved: the planet's weaker gravity and its lack of oceans. Once atmospheric conditions are ripe for a storm to spark, wind-borne dust remains aloft longer because of the planet's weaker gravitational pull. Mars has no bodies of water to moisten the air. The added humidity provided by Earth's oceans helps remove dust from the lower atmosphere and slow or prevent dust storms on from crossing continents. With no oceans, Mars dust blows hither and yon.