These days, even your smartphone’s camera can capture some amazing shots of the cosmos, as proven by this view of the Orion Nebula (M42) taken through a 12-inch telescope.

When I was 6 years old, my older brother helped me kick off my journey to becoming an amateur astronomer by taking me out to our backyard in southern Indiana and giving me tours of the night sky. Besides showing me the Moon, planets, and stars, he pointed out that the constellation Cassiopeia formed my initials: M and W. His passion for the cosmos is what first sparked my interest in astronomy and science in general.

Later, when I was a teenager in 1961, I received my first telescope as a Christmas present from my mother: an Edmund Scientific 3-inch f/10 Newtonian reflector. The following year, I started taking photographs through that telescope using her roll-film box camera — remember those? Over the next several years, I continued taking occasional astrophotos through the modest scope using a 35mm camera.

To take smartphone shots through a telescope, you can either mount the phone (above) or hold it by hand (below).

I earned a B.S. in astrophysics in 1970. However, I never became a professional astronomer. Instead, the degree was my ticket into the U.S. Air Force (USAF), where I served as both a jet fighter pilot and fighter pilot instructor, as well as a manager on the USAF Space Shuttle Program. Working with NASA in the early 1980s to prepare Vandenberg Air Force Base in California to launch and land the Space Shuttle Discovery on military missions was the beginning of my space career. After leaving the Air Force, I went on to work at a large aerospace company on several space-related projects.

It wasn’t until 1996, however, that I purchased my second telescope: a 3.5-inch f/13.8 Meade ETX Astro Telescope. Shortly after, I began using consumer digital point-and-shoot cameras to image the night sky, later moving on to digital single-lens reflex cameras with various ETX models and larger telescopes. Though I always considered myself an observer rather than an astrophotographer, I enjoyed experimenting with astroimaging. However, I never got into using dedicated imagers and I rarely connected a computer to my telescopes.

Then, in 2007, Apple released their first iPhone. As soon as I received it, I began to do smartphone astrophotography. And by upgrading my iPhone every two years, I have continued to pursue smartphone astrophotography with increasingly impressive results. To this day, I continue to enjoy using my iPhone to capture amazing images of the night sky with a Meade 12-inch f/8 LX600 telescope in my observatory in southern Arizona.

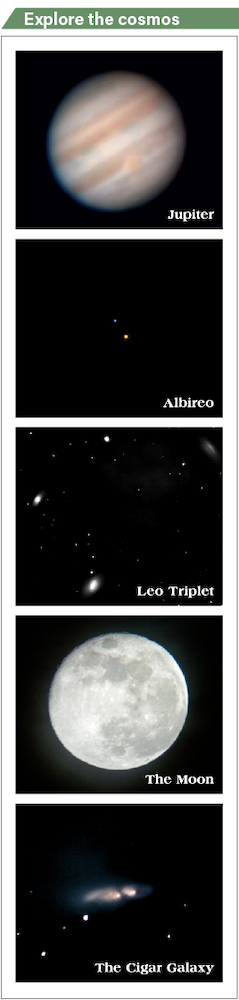

With a smartphone, the Sun, Moon, planets, asteroids, comets, stars, and even many deep-sky objects can be imaged without needing a connected computer or much, if any, post-processing. Plus, the images you capture can be immediately shared with your family and friends and posted on social media. Smartphone astrophotography also lets you easily record a snapshot of what you see through your telescope’s eyepiece. And since you likely already have a smartphone, why not use it for astrophotography?

Getting started

So, how do you do astrophotography with an iPhone — or any smartphone, for that matter?

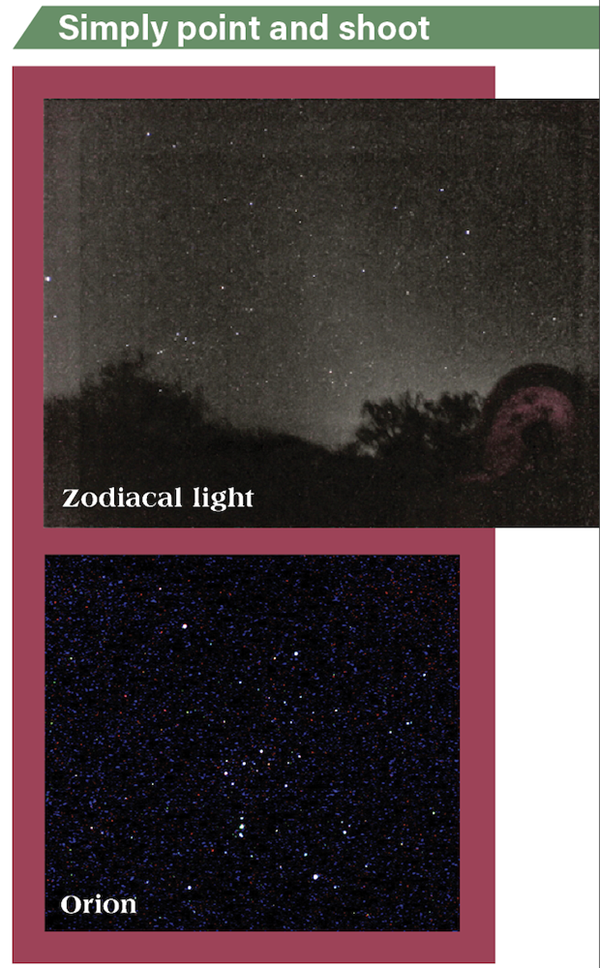

In the most basic sense, you just need a capable device. There are many recent smartphone models you can use to take handheld photographs of the night sky that can reveal the Moon, brighter stars, and even some planets. And on later model iPhones, the iOS Camera app in “Night Mode” will reduce or eliminate camera movement, letting you take exposures up to 30 seconds when photographing the night sky. For the best results, you should use a smartphone adapter to attach the phone to a camera tripod, a sky-tracking mount, or piggyback it on a tracking telescope. That will let you take long exposures that reveal the Milky Way, zodiacal light, constellations, and star trails (when tracking is off). There are similar apps on Android phones, too.

The next level of smartphone astrophotography is attaching your phone to an optical device, such as a spotting scope, binoculars, or a telescope. For bright objects like the Moon, you can simply hold the phone’s camera over the eyepiece and take a photo. But to get the best results, you should attach the phone to the eyepiece using a smartphone adapter, which are available for $20 to $100. Most adapters are universal and will fit the majority of smartphone models, so you can likely keep using the same one as you upgrade your smartphone to a newer model. However, other adapters are designed for specific phone models to accommodate unique sizes and camera lens locations. Some adapters include a ¼"-20 tripod mounting hole. There are some adapters that fit on only 1¼" eyepieces and others that fit on either 1¼" or 2" eyepieces. However, not all adapters will work on every 1¼" or 2" eyepiece, depending on the design and diameter of the eyepiece tube itself.

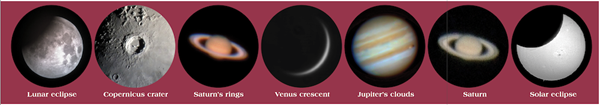

With only a smartphone attached to an eyepiece and a basic camera app, you can start taking photos of lunar eclipses, lunar craters, planets, the phases of Mercury and Venus, the changing positions of Jupiter’s four bright moons, bright asteroids, and countless stars. Add on a safe solar filter, and you can even photograph details on the Sun.

When attempting to snag bright planets, remember that you get the best images by taking a video recording and then stacking all the video frames using an astrophotography stacking program on a computer, such as Lynkeos (Macintosh) or Registax (Windows), both of which are free. Some smartphones allow you to set a fast frame rate, too, letting you capture up to 240 frames per second. With a frame rate that high, you can collect more than 2,000 video frames in just 10 seconds!

Target the varied worlds of our solar system.

Pushing the limits

To photograph fainter objects with a smartphone, you’ll need to deploy special apps designed for low-light conditions. Fortunately, some apps include functions specifically designed for smartphone astrophotography.

On my iPhone, I use an app called NightCap Camera. (Note: I have been a beta tester of NightCap Camera for many years.) The app gives you full manual control over your ISO setting (up to ISO 12,500), shutter speed (maximum one second), focus, camera lens selection, and white balance. It also has an intervalometer that allows you to automatically take multiple exposures. Finally, the app has special modes for taking long exposures, letting you capture star trails, satellite passes, and more. On Android phones, the free app DeepSkyCamera is designed for astrophotography and allows for manual exposure control for imaging.

NightCap Camera automatically stacks individual images to build up longer exposures than normally would be possible on the iPhone. For example, 60 one-second exposures of a faint nebula or galaxy are merged into an image roughly equivalent to a single one-minute exposure. NightCap Camera, however, does not register stars, so an accurate tracking mount or autoguider is required for long exposures. On Android phones, the free app SpiralCam will image and stack faint objects. You’d be surprised what amazing images your phone can capture with long exposures!

Quick Tip: Adding a clip-on fisheye lens will let you take a dramatic shot of the International Space Station passing through the sky.

Apps such as NightCap Camera will also greatly expand the objects your smartphone can photograph. Star clusters are good initial targets to help you learn how to capture faint objects using your phone. For instance, with a wide-field eyepiece, you can image both members of the Double Cluster (NGC 869/84). Bumping up the magnification will reveal globular clusters like the Great Globular Cluster in Hercules (M13). Bright planetary nebulae like the Ring Nebula (M57) are also good smartphone targets, while fainter ones like the Blue Snowball (NGC 7662) and the Lion Nebula (NGC 2392) are slightly more challenging to capture. Similarly, the Crab Nebula’s (M1) low surface brightness makes imaging it a difficult task.

As long as you don’t expect Hubble-quality images, your smartphone can also photograph galaxies. However, as with the Crab Nebula, galaxies with low surface brightness are difficult to get good shots of. The bright Andromeda Galaxy (M31), for instance, will only show its central core and a hint of its spiral arms, even with a wide-angle view. However, taking individual long exposures of galaxies and then stacking the images on a computer can often bring out more details and colors. If your smartphone astrophotography app supports it, using Raw mode will allow more post-processing control and better stacking results. NightCap Camera does not currently support Raw, but it does save images as TIFFs, as well as JPEGs and high-quality JPEGs.

Your phone can also snag many other types of cosmic objects that might surprise you. I suggest letting your imagination go wild. As a general rule of thumb, if you can see it through your telescope, you can probably image it with your smartphone.

Binoculars offer another easy (and affordable) way to enhance your smartphone’s view of the cosmos.

Honing your phonecraft

Now that we’ve covered both beginning and more advanced techniques, here are a few final tips that will help improve your smartphone astrophotography.

Most smartphones allow you to use the volume control on your earbuds to remotely release the shutter, or you can use a Bluetooth-based remote shutter release. When paired with an iPhone, an Apple Watch can also act as a remote shutter release. Using any of these will prevent the blurring that often plagues photographers who rely on manually pressing the on-screen shutter button when taking astroimages with their smartphone, especially long exposures.

Make sure to focus the object in the telescope by physically looking through it before putting the phone camera to the eyepiece. Generally, you should have your camera focused at infinity. And, ideally, you’ll want to set up the camera lens at the same distance as the eyepiece’s eye relief to maximize the camera’s field of view.

But be warned: Aligning the camera lens properly over the eyepiece during afocal imaging — the only way you can use your smartphone for astrophotography through a telescope — is a challenge with universal smartphone adapters. If you can see the outline of your eyepiece’s field of view on the phone’s live preview screen, then it’s easy to get the camera aligned. However, if you are trying to image a faint object in a dark sky, you may not see anything on your phone’s screen at all. Shining a red light into the telescope aperture will help illuminate the field, letting you align the smartphone adapter. Another option is removing the eyepiece — with the adapter and phone attached — from the telescope and pointing it at a light source to help you properly adjust it.

Star trails (as well as satellites or passing planes) are relatively easy to capture with your smartphone by taking long exposures — no telescope or binoculars required. However, you will need to make sure your phone remains motionless while its shutter is open and collecting light.

The auto-exposure function of some phones and apps may overexpose bright objects like the Moon, Venus, and Jupiter. However, most apps — even built-in ones — will allow you to make some manual adjustments. First, once the view is as crisp as you can make it, lock the focus. Then adjust the exposure to get the best-looking image on the live preview screen that you can and lock the exposure. If the object is still too bright even after manual adjustments, you can use a Moon filter or a polarizing filter on the eyepiece to reduce the object’s brilliance. Finally, as it can be difficult to see if your exposure is correct on the small phone screen, bracket the images using different exposures (ISO, shutter speed) to ensure you get a proper exposure.

Set your telescope to a low magnification and use the phone’s “normal” (1x) lens to maximize the brightness of faint objects. Higher magnifications can be used for targeting globular clusters and bright planetary nebulae. Sometimes the smartphone camera’s digital zoom or the use of a telephoto lens may improve the image, but these should not normally be employed. Digital zoom just magnifies the pixels without increasing details and a telephoto lens reduces the object’s brightness. Implementing a low ISO value and a fast shutter speed is a great approach for targeting bright stars. Meanwhile, a high ISO value and slow shutter speed — combined with a long exposure and light boost in NightCap Camera — will let you capture fainter nebulae and galaxies.

A clean eyepiece is necessary to avoid dust doughnuts in your image, especially when photographing the Moon. Keeping the eyepiece eyecup attached also helps your shots by preventing stray light from reaching the camera lens, but you might need to remove the eyecup to use some adapters.

The most important advice I can give you is to ensure the smartphone adapter is tight on the eyepiece and that the phone is secure on the adapter — or make sure your phone is insured against damage. As your telescope slews from one object to the next, the phone’s position can change significantly, most notably when using an equatorially mounted telescope, making slippage more likely.

For the best results when taking long exposures, you should attach your phone to a sturdy tracking mount or tripod using a smartphone adapter.

Lastly, experiment, experiment, experiment — and do not get frustrated during your first attempts.

Current smartphones have amazing cameras, and apps can further extend their low-light capabilities. This makes smartphone astrophotography accessible to everyone. Join the fun — you might be surprised by what your phone can capture!

Find our variety of helpful tools and accessories HERE

Source: astronomy.com