The Moon moves through Earth’s umbra — from right (west) to left (east) — in this composite assembled from multiple exposures taken during the Jan. 20, 2019, total lunar eclipse. Although this month’s event will not be a total lunar eclipse, at 97 percent coverage, it will still be a stunning sight.

On Friday, Nov. 19, the Sun, Earth, and the Moon (in that order) will line up and most of Moon will trek through Earth’s umbra, the darkest part of its shadow. Although this won’t be a total lunar eclipse, it’ll be darn close. At mid-eclipse, 97 percent of our only natural satellite will be covered by Earth’s umbra.

Observers with clear skies should be able to spot nearly all the effects that are visible during a total lunar eclipse. This wouldn’t be the case if it were a partial solar eclipse (with 3 percent of the Sun’s face uncovered, you would miss out on Baily’s beads, diamond rings, and the solar corona). In other words, we’re lucky Luna is the star of this month’s show.

Who will see it?

Anyone located on the nighttime side of our planet during this eclipse will catch at least some of it. Observers throughout North America will have the prime views, with only people along the Atlantic coast missing the Moon’s passage through the penumbra (the lighter, outer part of Earth’s shadow), which usually isn’t visible anyway.

South American residents will witness some of the partial eclipse, as will those throughout Australia and central and eastern China. Inhabitants of eastern India and western China will see only some of the penumbral eclipse. Meanwhile, like North America, eastern Russia will have a view of the whole event. Unfortunately, none of the eclipse will be visible for most of Europe and Africa.

The Moon is fully shrouded by Earth’s umbral shadow in this mid-totality shot taken Sept. 27, 2015.

When and where?

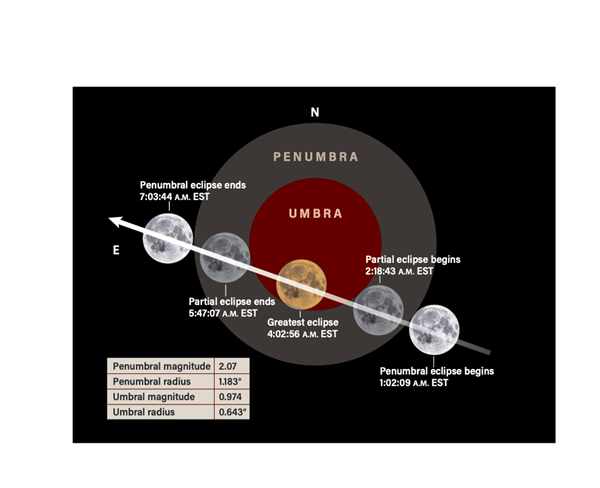

The start of the eclipse, when the Moon first touches our planet’s penumbra, occurs at 1:02:09 a.m. EST. Luna enters the umbra beginning at 2:18:43 a.m. EST and leaves it at 5:47:07 a.m. EST. The eclipse officially ends when the Moon departs the penumbra at 7:03:44 a.m. EST. Greatest eclipse, at which point the Moon is as deep in Earth’s umbra as it will get, occurs at 4:02:56 a.m. EST.

Throughout the event, the Moon will stand in front of the stars of the familiar constellation Taurus the Bull. Our satellite’s ever-changing apparent diameter at the time will be nearly 29.47'. That’s smaller than its average diameter because this eclipse occurs only 1.7 days before the Moon reaches apogee, the point in its orbit that takes it farthest from Earth. A smaller, more distant Moon takes longer to traverse our planet’s shadow. In fact, even though the Moon doesn’t pass through the center of Earth’s umbra this time, our satellite will still spend nearly 3.5 hours traversing it. And all told, the Moon will spend a whopping 6 hours moving through Earth’s penumbra.

At mid-eclipse, which astronomers often call the instant of greatest eclipse, the Moon will lie overhead at a point in the Pacific Ocean east of the Hawaiian Islands, at approximate coordinates 140° west longitude and 20° north latitude.

Just how dark will this eclipse be?

Ah, here’s the question many observers are asking. The eclipse on Nov. 19 will not be total. Some 2.58 percent of the Moon’s surface will stay outside the umbra. Even that region, however, will fall within the darkest part of the penumbra.

If you’ve ever glimpsed a 3-percent-illuminated crescent Moon, you know its brightness comes nowhere near that of the Full Moon. Remember, though, that a thin crescent reflects sunlight at an oblique angle to our eyes. Indeed, even a Quarter Moon reflects only 10 percent as much light toward Earth as a Full Moon. But during the eclipse, the Sun will be directly behind us, so the illuminated portion of the Moon will be reflecting that sunlight straight back at us.

We also have to account for the part of the Moon covered by the umbra. It won’t disappear, but rather should look fairly bright compared to other total lunar eclipses. A good estimate of the Moon’s brightness at mid-eclipse is about magnitude –5; it will be brighter than Venus (–4.7), but only 0.1 percent the brightness of the Full Moon.

The photographer captured himself observing a total lunar eclipse from near the Alberta-Saskatchewan border in Canada on Jan. 20, 2019. The Beehive Cluster (M44) sits just to the left of the eclipsed Moon, while Orion is clearly visible toward the right of the frame.

Because the Moon during this eclipse will pass through a large range of the shadow’s depths, its appearance will change significantly with time. For the first half of the eclipse, the umbra will simply appear black. But as it covers more of the Moon’s face, the contrast between it and the section remaining in sunlight will lessen.

Our atmosphere also plays a part in how dark any lunar eclipse gets. The air contains water droplets and solid particles like dust and ash, which reduce its transparency. A large volcano erupting before a lunar eclipse can darken the Moon’s face considerably by filling the atmosphere with opaque particles. Finally, if there are many clouds along the edge of our planet, not as much sunlight will filter through to the Moon.

In addition to appearing dark, the Moon takes on a particular color before totality. This occurs because Earth’s atmosphere bends some of the Sun’s rays into Earth’s shadow. And because air preferentially scatters the shorter (bluer) wavelengths of that light, it produces a reddening effect while darkening the Moon’s face.

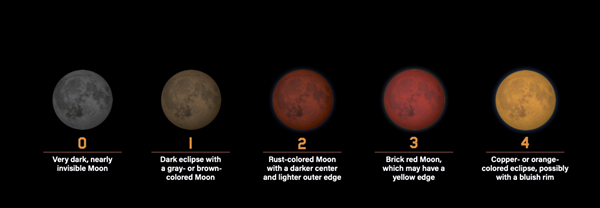

Observers estimate the darkness of any total lunar eclipse by using a five-point scale developed in 1921 by French astronomer André-Louis Danjon. He called the brightness of maximum totality (although using the word “darkness” wouldn’t be wrong here) the luminosity (L) of the eclipse. You can estimate L with your naked eyes, binoculars, or a telescope. Just be sure to make your evaluation at around 4:03 a.m. EST, which is near the time of maximum for this eclipse.

The color the Moon takes on during lunar eclipses varies. Astronomers use the Danjon scale to rate the Moon’s look, which can run from nearly invisible to rusty red to copper-orange.

The five values of L in Danjon’s system describe the brightness the Moon’s surface during totality. If L=0, the Moon is quite dark, almost invisible at mid-totality. If L=1, the Moon appears gray or brown, and details are tough to pick out. If L=2, the Moon looks deep red or rusty, with those regions nearest the umbra appearing quite dark while those farthest from its center appear brighter, sometimes significantly so. If L=3, the Moon’s color is brick red and the shadow often has a bright edge that sometimes takes on a yellow hue. Finally, if L=4, the Moon is a bright copper-red or orange and the umbra’s bright edge often looks blue.

Remember, though, that these numbers are for total lunar eclipses. It’s certain that L for this partial eclipse won’t be 0, 1, or 2; most observers predict L=4. But if it’s a bit darker, how many observers will assign it a value of 3? If you do make more than a naked-eye estimate of L, be sure to note the size and magnification of the binoculars or telescope you used and the time. That will help you compare your result with others after the event.

Amateur astronomers probably will go a bit farther than this. If you want to record the event in more detail, start by documenting any changes in color or brightness within different parts of the shadow. Also document the sharpness of the shadow’s edge. Especially note how easy it is to see various craters, seas, and mountain ranges in the umbra-covered portion of the lunar surface. As a reminder, this event lasts hours, so you’ll have time to do it all.

A total lunar eclipse stands above a blanket of clouds wafting off a peak of the Continental Divide in the Canadian Rocky Mountains of southwest Alberta. The photographer captured this shot just before dawn on Jan. 31, 2018, as the eclipsed Moon was setting in the west.

You even could make a few sketches, which will help you remember the features you saw. Although most people will photograph the event, keep in mind that images don’t really capture what your eyes see, while sketches do.

All ’round the Moon

The constellations of the Northern Hemisphere’s late fall and winter surround this month’s Full Moon. And because the eclipse occurs in the early morning hours in the U.S., the brightest constellations will ride high in the west and south. The Moon will make its coolest close pairing with the Pleiades (M45), which will lie some 5½° north of our satellite at mid-eclipse. This bright star cluster will appear even brighter as Earth’s umbra progresses across the Moon’s face. Aldebaran (Alpha [α] Tauri) will lie 14° east of the Moon and the magnificent constellation Orion the Hunter will stand 35° to Luna’s southeast.

The sky’s brightest star, magnitude –1.46 Sirius (Alpha Canis Majoris), will be 60° from the Moon, standing one-third of the way from the horizon to the zenith. Four more of the sky’s top 25 brightest stars to seek out during the eclipse will be Capella (Alpha Aurigae), Castor and Pollux (Alpha and Beta [β] Geminorum, respectively), and Procyon (Alpha Canis Minoris).

A “totally” safe event

Often, when we hear or read the word eclipse, it’s followed by some kind of warning to protect your eyes. That’s an important disclaimer for solar eclipses, but a lunar eclipse is not dangerous in any way. Your eyes are safe because you’re simply watching the Moon pass through Earth’s two-part shadow. You might also get a better view through binoculars or a telescope — no filter required — which are both totally safe to use for this event. Do note, however, that for most of the U.S., the early hours of Nov. 19 will likely be cold, so bundle up. It also might be a tough sell to throw a viewing party for this eclipse. But if you’re looking for one, lots of astronomy clubs and science centers will be hosting them.

This eclipse showcases easy science that comes from what I like to call sublime celestial geometry. So, head outside for at least a short time to watch our planet line up with its most significant cosmic neighbors. Enjoy the show!

Source: Astronomy Magazine