|

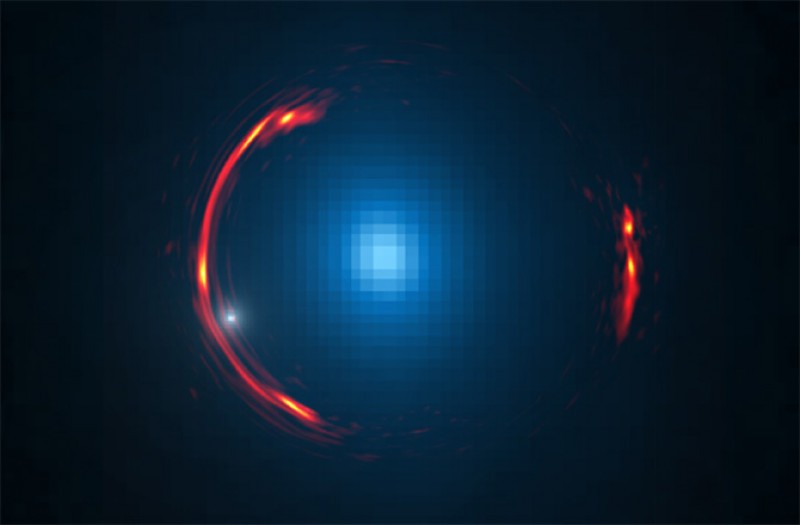

| Composite image of the gravitational lens SDP.81 showing the distorted ALMA image of the more distant galaxy (red arcs) and the Hubble optical image of the nearby lensing galaxy (blue center object). By analyzing the distortions in the ring, astronomers have determined that a dark dwarf galaxy (data indicated by white dot near left lower arc segment) is lurking nearly 4 billion light-years away.

Y. HEZAVEH, STANFORD UNIV.; ALMA (NRAO/ESO/NAOJ); NASA/ESA HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE |

There are few things that get us more excited than the mysteries of dark matter and the warping of spacetime, but when you have both wrapped into a stunning image of an Einstein ring, you know you’re onto something special.

In 2014, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile observed a striking cosmic quirk during its Long Baseline Campaign. It saw a distant galaxy, warped beyond recognition, by the gravitational field of a massive galaxy in the foreground. This “Einstein ring” is so-called after Einstein’s theory of general relativity, which predicts spacetime can become bent by the presence of a powerful gravitational field.

In this case, the foreground galaxy had drifted in front of the more distant galaxy located some 12 billion light-years away, causing the distant galaxy’s light to be redirected around the warped spacetime. The result was a near-perfect circle of galactic light received by ALMA as one of the more extreme examples of gravitational lensing. Gravitational lensing is common in observations of the deep cosmos, where massive galaxies and galactic clusters bend spacetime like a malleable rubber sheet, often creating a “funhouse” mirror-like effect, distorting the observed shapes of distant galaxies whose light has taken a helter-skelter path through the confused spacetime landscape.

But sometimes, as this example proved, the alignment can be so perfect that the distant galaxy’s light can be warped around the symmetrical foreground galaxy, creating a ring that resembles a candle flame passing behind a magnifying glass. Gravitational lenses are the universe’s natural magnifying lenses and they are being used by the Hubble Space Telescope, for example, to superboost its observational power as part of the Frontier Fields project.

Though it looks like a pristine ring, this particular observation of the “SDP.81″ gravitational lens holds some tiny distortions in the shape of its ring and astronomers have used these distortions to reveal the presence of an invisible dwarf galaxy situated right next to the more massive lensing galaxy. And this tiny cluster of stars is packed with dark matter.

“We can find these invisible objects in the same way that you can see rain droplets on a window,” said Yashar Hezaveh at Stanford University, Calif., in a statement. “You know they are there because they distort the image of the background objects.” Raindrops will subtly refract light, distorting the light passing through a window; in much the same way, the invisible dwarf galaxy’s gravitational field is creating a minute distortion in the Einstein ring, revealing its presence in a tiny spacetime warp.

|

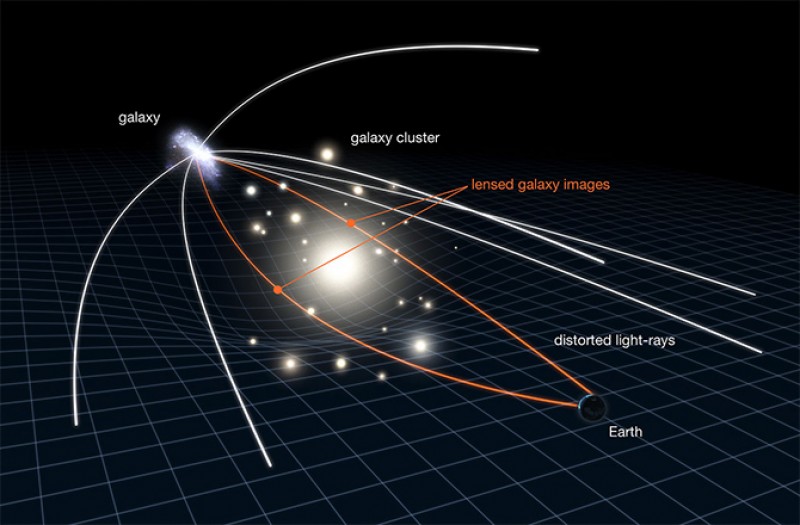

| This diagram provides a good description as to how gravitational lensing works. Light from a distant galaxy travels through spacetime as it curves around a cluster of galaxies in the foreground. Interestingly, the mass of the foreground cluster has a similar effect on this distant light as a glass lens would have if placed in front of a candle flame. Should the positioning be just right, the gravitational lens can amplify the distant light, creating a natural lens in space, magnifying the light from distant galaxies that would have otherwise remained too faint to be seen. It is this effect of gravitational lenses that is being leveraged by Hubble astronomers who have embarked on a project called " Frontier Fields " that is on the lookout for cosmic lenses to superboost Hubble's observing power. ESA |

Finding this distortion and realizing it was due to the presence of an unseen galaxy was no easy task and required a huge computational effort, requiring, in part, time on one of the world’s most powerful supercomputers, the National Science Foundation’s Blue Waters.

Because of its close proximity to the larger galaxy, its estimated mass and lack of optical data, Hezaveh’s team thinks they’ve found a very dim dwarf galaxy that is dominated by dark matter.

Read more: discovery.com