Far from the blaring cacophony of cities, towns and suburbs, there are far quieter soundtracks to be found — the murmurs of wind rustling grasses, rushing waves tumbling onto beaches, the creaking of tree branches and trunks.

But underneath all that is yet another soundscape, a permanent, low-frequency drone produced by Earth itself, from the vibrations of ongoing, subtle seismic movements that are not earthquakes and are too small to be detected without special equipment.

Earth is "humming." You can't hear it, but it's ongoing. And now scientists have measured that persistent hum from the ocean floor, for the first time. [What's That Noise? 11 Strange and Mysterious Sounds on Earth & Beyond

Far from the blaring cacophony of cities, towns and suburbs, there are far quieter soundtracks to be found — the murmurs of wind rustling grasses, rushing waves tumbling onto beaches, the creaking of tree branches and trunks.

But underneath all that is yet another soundscape, a permanent, low-frequency drone produced by Earth itself, from the vibrations of ongoing, subtle seismic movements that are not earthquakes and are too small to be detected without special equipment.

Earth is "humming." You can't hear it, but it's ongoing. And now scientists have measured that persistent hum from the ocean floor, for the first time. [What's That Noise? 11 Strange and Mysterious Sounds on Earth & Beyond

Most of the movements in the ground under our feet aren't dramatic enough for people to feel them. Earthquakes, of course, are the big exception, but Earth undergoes far more earthquakes globally than you might suspect — an estimated 500,000 per year, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Of those, 100,000 are strong enough to be felt, and about 100 of those are powerful enough to cause damage.

But even in the quiet periods between earthquakes, there's a whole lot of shaking going on.

Since the 1990s, researchers have known that Earth is constantly vibrating with microseismic activity, known as "free oscillation," scientists reported in a new study describing new recordings of the phenomenon. Free oscillation creates a hum that can be detected anywhere on land by seismometers — equipment used to detect and record vibrations.

For years, the source of this perpetual humming stymied researchers, with some suggesting that the rhythmic ebb and flow of ocean waves that reached all the way down to the seafloor were responsible, while others attributed the vibration to collisions between ocean waves. Then, in 2015, scientists determined that both types of ocean movement played a part in keeping Earth vibrating, Live Science previously reported.

While seismologists have recorded and measured Earth's hum on land, they had yet to capture evidence of the planet's sonic stylings from the ocean depths — until now.

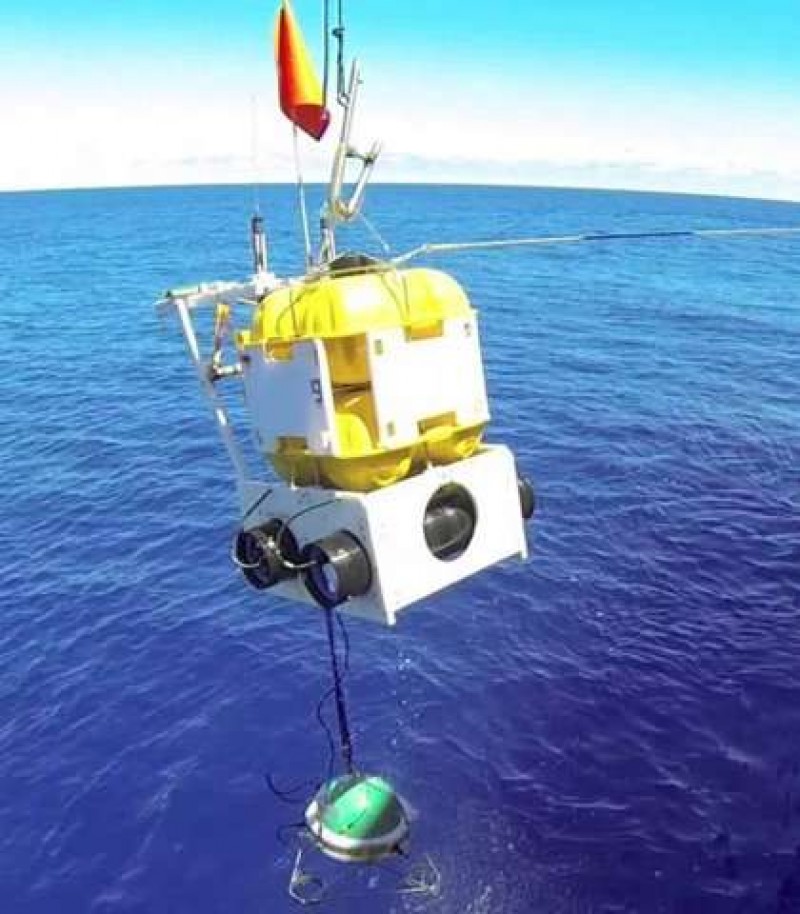

Recently, scientists traveled to the seafloor in the Indian Ocean to capture the humming sound, using special spherical ocean seismometers. Between September 2012 and November 2013, the researchers deployed 57 free-fall seismometers around La Réunion Island to the east of Madagascar, over an area measuring about 772 square miles (2,000 square kilometers), they wrote in the study.

Using filters, noise reduction and calculations, they isolated the hum from normal ocean noise levels generated by ocean wave motion and seafloor currents, and found "very clear peaks" that appeared consistently over the 11-month study period, and which appeared in the same amplitude range as measurements of the humming taken on land in Algeria, the scientists reported. They noted that the peaks occurred at several frequencies between 2.9 and 4.5 millihertz — about 10,000 times lower than the human hearing threshold, which is 20 hertz.

Capturing ocean recordings of Earth's hum will provide scientists with far more data than is currently available from readings taken on land, contributing to efforts to map the planet's interior, the researchers wrote in the study.

Source: Mindy Weisberger