How to view Pluto at opposition this week

Prior to New Horizons’ flyby of Pluto in 2015, the best images of the dwarf planet (left) and its moon Charon (right) were taken by the Hubble Space Telescope — and they resolved little more than blurry bright and dark patches. Fortunately, New Horizons brought these features into crisp view.

On July 14, 2015, the New Horizons probe swept within 7,700 miles (12,400 kilometers) of Pluto’s surface. With the flyby, features that the Hubble Space Telescope previously saw as fuzzy spots suddenly resolved into broad canyons, flowing ice, expansive craters, mountains of frozen water, and a giant glacier only 10 million years old. The spacecraft proved that Pluto is still a geologically active world, but it also provided a list of questions that will take scientists decades to answer.

Still, researchers aren’t the only ones entranced by the wondrous world of Pluto — amateur astronomers across the globe are eager to check the dwarf planet off their observing bucket lists. Luckily, this summer, Pluto moves into prime position. Well, about as prime as it gets for the distant dwarf planet.

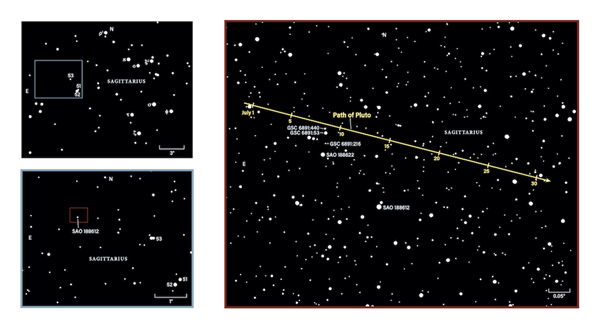

Pluto is seen here crossing the rich star fields of the constellation Sagittarius the Archer on June 29, 2014. The photographer captured this four-minute tracked exposure at around 3:50 a.m. CDT from Dexter, Iowa.

Prepare for the hunt

Because Pluto glows dimly at magnitude 14.3 and appears as a mere point of light through any telescope, simply identifying it brings a sense of satisfaction. But to see it, you need the right telescope, a dark site, and the star charts that accompany this story.

The frozen world reaches opposition July 17. At that point, it lies opposite the Sun in our sky and is visible all night. Pluto’s visibility changes so slowly, however, that it remains just as easy to spot for a few weeks on either side of this peak date. That’s good, because the 17th is the date of the First Quarter Moon, which will scatter enough light throughout Earth’s atmosphere that it will make finding Pluto difficult. Better to try to find it within a few days of July 9, the date of New Moon. On that date, Pluto will be only 0.008 magnitude fainter than it will be at opposition — in other words: no difference.

An 8-inch telescope will be enough to reveal Pluto, although a larger instrument, which collects more light, will make the task quite a bit easier. Once you’ve got your gear lined up, locate an observing site that isn’t simply dark, but also has good seeing, or atmospheric steadiness.

Track down Pluto

On July 9, the dwarf planet lies in eastern Sagittarius, 3.5° west of the globular cluster M75. Its right ascension is 19h51m, and its declination is –22°35'. Pluto takes about 248 years to orbit the Sun once, and it has been strolling through this constellation since December 2009. It won’t enter the neighboring one, Capricornus, until early 2024.

Top: Eastern Sagittarius stars down to magnitude 6.2 are shown in this naked-eye view. Pluto spends July roughly 10° northeast of Tau (τ) Sagittarii, the lower left corner of the handle of the Teapot asterism.

Bottom: This binocular view shows stars down to magnitude 8.7. Use it to pinpoint magnitude 7.8 SAO 188612, located 2.5° east-northeast of 6th-magnitude 53 Sagittarii.

Right: Pluto moves slowly westward this month, passing 64” northeast of the magnitude 13.5 star GSC 6891:440 on the night of July 9/10. This telescope view shows stars to magnitude 15.0.

Use the charts on pages 48 and 49 to help you to pick out the world from the background stars. But make sure to use a dim red light to illuminate these charts. That color has the least impact on dark adaptation of your eyes, though even red light will ruin your night vision if it’s too bright.

Start with the naked-eye view at the top of this page and identify the handle of the main asterism in Sagittarius: the Teapot. Starting with magnitude 3.3 Tau (τ) Sagittarii — the star that marks the lower left corner of the Teapot’s handle — move 7° northeast and find a pair of stars about ¼° apart. They are 51 and 52 Sagittarii (Sgr), which glow at magnitudes 5.6 and 4.7, respectively. An easy way to gauge a 7° angular distance is to use 7x50 binoculars, whose field of view is 7° wide.

From 52 Sgr, move 1.7° north-northeast to 6th-magnitude 53 Sgr, a close double star. Target 53 Sgr in your binoculars (see the bottom map on this page), then head east and a bit north almost 2.5° to SAO 188612. This star glows at magnitude 7.8 and is the brightest in the area. Center it in your telescope at 11 p.m. EST.

The next brightest star in the region, SAO 188622 (see the telescopic chart on page 49), glows at magnitude 9.9 and is 11' northeast of SAO 188612. Still with me? Hang in there, we’ve almost arrived. From SAO 188622, a slightly curved line of stars meanders northward. First is magnitude 15.0 GSC 6891:216. If you can see this star, you’ll definitely make it to Pluto. Next, head north to magnitude 12.4 GSC 6891:53, then a little farther north to magnitude 13.5 GSC 6891:440. Finally, Pluto’s path takes the world just 64" to the northeast of GSC 6891:440.

Over the next few hours, Pluto will trek slightly westward. Outer planets generally move to the east through the stars. But around opposition, Earth overtakes Pluto, causing the dwarf planet to appear to travel westward. This apparent reversal is called retrograde motion. So, if you check the positions of the objects in your field of view every hour or two, one will change its position slightly in relation to GSC 6891:440. That’s your target.

The telescopic chart shows all background stars down to magnitude 15, so you should be able to locate Pluto, which glows slightly brighter than this limit. If you can’t tell which point of light it is, sketch the stars in the field of view you think is centered on the dwarf planet. Then, at least three nights later, revisit this field and create a second sketch. If you notice that one of the “stars” has moved, you’ve found Pluto.

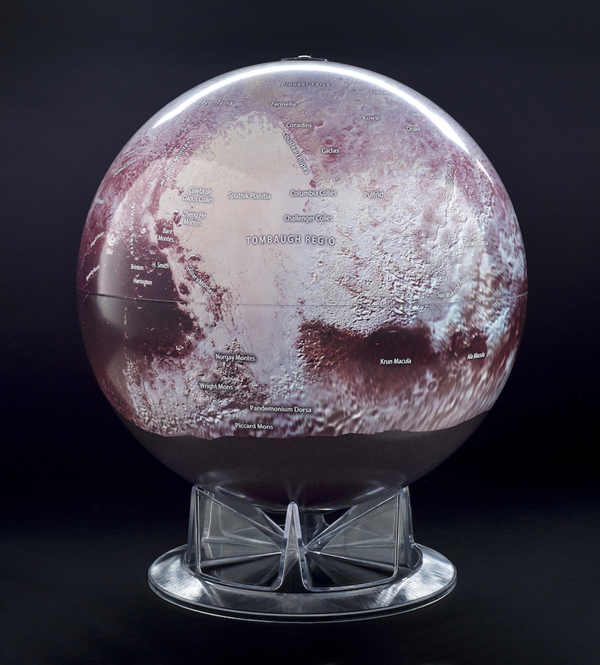

Astronomy magazine’s Pluto globe

As soon as the New Horizons spacecraft began to send data — especially photographs — back to Earth, former Astronomy Senior Editor Michael E. Bakich started thinking about creating the very first globe of the distant world. He knew it would be popular with our readers.

Bakich initially contacted New Horizons Principal Investigator S. Alan Stern, who directed him to Ross A. Beyer, an affiliate of New Horizons’ Geophysics Imaging Team.

Beyer collected and organized the data and circulated drafts of the maps among his team for comments and approval. He also worked with Astronomy Art Director LuAnn Williams Belter to make sure the features were displayed correctly, the hemispheres lined up, and the color was correct.

Try spotting Charon

Full disclosure: To search for Pluto’s largest moon, Charon, you will need a 20-inch scope. First, Charon is two magnitudes fainter than Pluto. And second, the separation between the two bodies is never more than 0.8".

Charon orbits Pluto once every 6.3872 days. Use the orbital diagram at the bottom of page 49 to figure out where the moon lies relative to the planet on any July night. The included table lists the times of the moon’s greatest northern elongations. The current geometry of the system places the satellite farthest from Pluto when it sits either north or south of the dwarf planet, though its orbit appears nearly circular from our vantage point.

To hunt for Charon, calculate how much time has elapsed since its previous greatest elongation. So, let’s say you want to try to observe the moon at 11 p.m. EDT on July 9. The table shows that Charon’s previous northern elongation occurred July 7 at 8:54 a.m. EDT, so two days and 14 hours have passed since greatest elongation.

Then, consult the orbital diagram to figure out Charon’s approximate location along its orbit about 2.6 days after greatest northern elongation. If you see a faint speck there, you’ve found Charon. But to be sure, watch it for several hours to see if it keeps pace with Pluto as the system moves past GSC 6891:440. The farther from Pluto the moon appears, the easier it is to spot. The illustration shows south at the top to match the view through most telescopes when Pluto lies highest in the sky.

Relatively few amateur astronomers have ever seen Pluto. So, even though the process is a bit difficult, you’ll feel a sense of accomplishment having done it. And as to the question of whether Pluto is a planet, decide for yourself when you catch it in your scope. Good luck!

Source: Astronomy Magazine