|

|

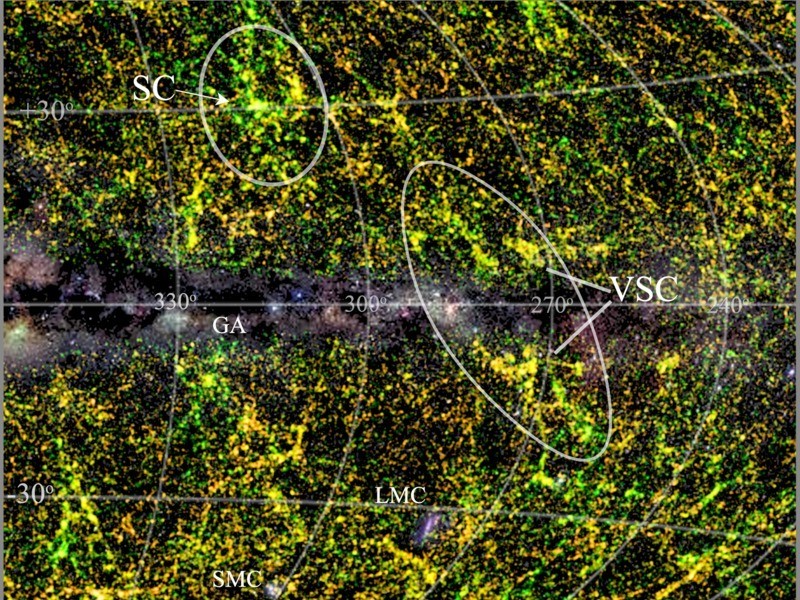

The Vela supercluster in its wider surroundings: The image displays the smoothed redshift distribution of galaxies in and around the Vela supercluster (larger ellipse; VSC). The centre of the image, so-called the Zone of Avoidance, is covered by the Milky Way (with its stellar fields and dust layers shown in grey scale), which obscures all structures behind it. Colour indicates the distance ranges of all galaxies within 500 - 1000 million light years (yellow is close to the peak of the Vela supercluster, green is nearer and orange further away). The ellipse marks the approximate extent of the Vela Supercluster, crossing the Galactic Plane. The VSC structure was revealed thanks to the new low latitude spectroscopic redshifts. Given its prominence on either side of the plane of the Milky Way it would be highly unlikely for these cosmic large-scale structures not to be connected across the Galactic Plane. The structure may be similar in aggregate mass to the Shapley Concentration (SC, smaller ellipse), although much more extended. The so-called “Great Attractor” (GA), located much closer to the Milky Way, is an example of a large web structure that crosses the Galactic Plane, although much smaller in extent than VSC. The central, dust-shrouded part of the VSC remains unmapped in the current Vela survey. Also visible are the Milky Way’s two satellite galaxies, LMC and SMC, located south of the Galactic plane. Image credit: Thomas Jarrett (UCT)

|

Superclusters are the largest and most massive known structures in the Universe. They consist of clusters of galaxies and walls that span up to 200 million light-years across the sky. The most famous supercluster is the Shapley Supercluster, some 650 million light-years away containing two dozens of massive X-ray clusters for which thousands of galaxy velocities have been measured. It is believed to be the largest of its kind in our cosmic neighbourhood.

Now a team from South Africa, the Netherlands, Germany, and Australia including two scientists at the Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik in Garching, has discovered another major supercluster, slightly further away (800 million light-years distant), which covers an even larger sky area than Shapley. The Vela supercluster had gone unnoticed due to its location behind the plane of the Milky Way, where dust and stars obscure background galaxies, resulting in a broad band void of extragalactic sources. The team’s results suggest the Vela supercluster might be as massive as Shapley, which indicates that its influence on local bulk flows is comparable to that of Shapley.

The discovery was based on multi-object spectroscopic observations of thousands of partly obscured galaxies. Observations in 2012 with the refurbished spectrograph of the Southern African Large Telescope (SALT) confirmed that eight new clusters reside within the Vela area. Subsequent spectroscopic observations with the Anglo-Australian Telescope in Australia provided thousands of galaxy redshifts and revealed the vast extent of this new structure.

Prof Renée Kraan-Korteweg from the University of Cape Town, who led this study and has been investigating this region for more than a decade, says: “I could not believe such a major structure would pop up so prominently,” when she and her colleagues analysed the spectra of the new survey.

Scientists Hans Böhringer and Gayoung Chon from the Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik in Garching have surveyed the supercluster region for X-ray luminous galaxy clusters and found two massive clusters in the region covered by the redshift survey and further massive clusters in the immediate vicinity. They thus confirm: “This discovery shows that the Vela supercluster has a significantly higher matter density than average, making it a prominent large structure.”

But there is still much to do – further follow-up observations are needed to unveil the full extent, mass, and influence of the Vela supercluster. So far this region of the sky is sparsely sampled, while the part closest to the Milky Way has not been probed because dense star and dust layers block our view.

Read more: mpe.mpg.de