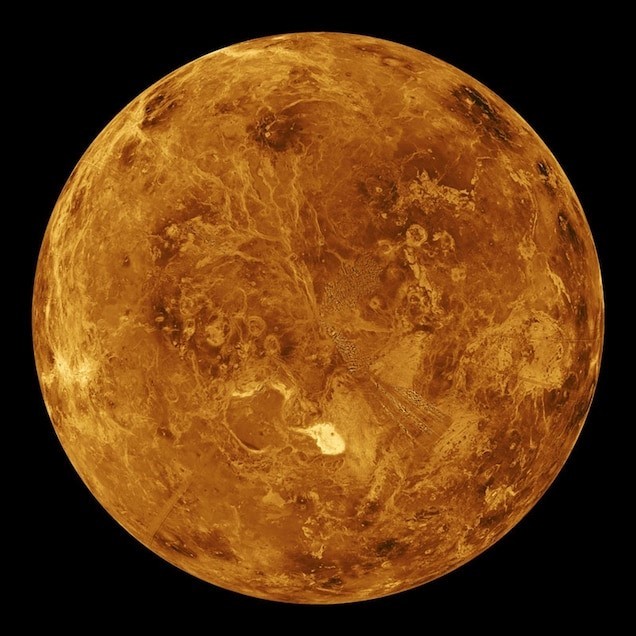

NASA will head to Venus for first time in roughly 30 years

Two spacecraft aim to solve deep mysteries about the nearby planet, including why it resembles a hellish, toxic version of Earth.

NASA had a surprise in store for planetary scientists today: During a “State of NASA” briefing, the agency announced that roiling, toxic Venus will be the target of the next two missions in its highly competitive Discovery program.

“These two sister missions, both aimed to understand how Venus became an inferno-like world capable of melting lead at the surface—they will offer the entire science community the chance to investigate a planet we haven’t been to in more than 30 years,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said during the briefing. “We hope these missions will help further our understanding of how Earth evolved and why it’s currently habitable, when other [rocky planets] in our solar system are not.”

One spacecraft, called DAVINCI+, will study the planet’s toxic atmosphere—a thick shroud of carbon dioxide and sulfuric acid clouds. The other, VERITAS, will make detailed maps of the planet’s surface and try to reconstruct its geologic history.

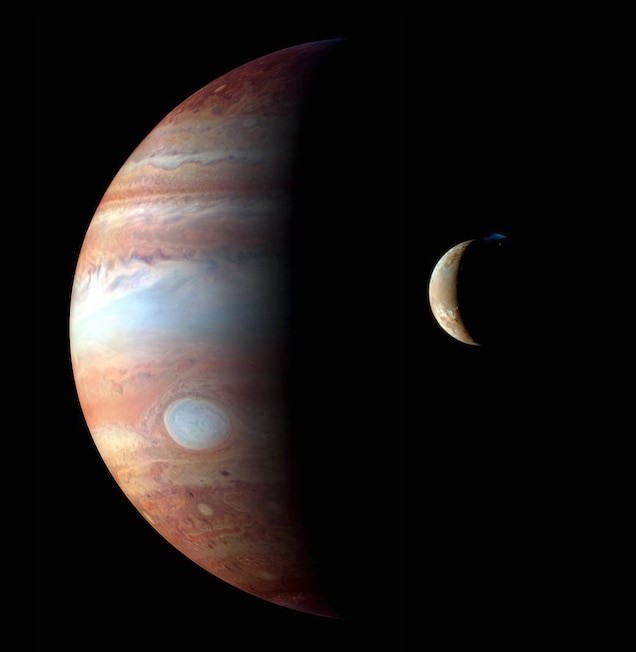

The pair beat out two other finalists, which would have sent probes to Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io or Neptune’s moon Triton—destinations that have been high on planetary science wish lists for decades.

NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft recorded this view of Jupiter’s moon Io, and one of its erupting volcanoes, during an encounter with Jupiter in 2007 on the way to Pluto.

The announcement comes amid surging interest in a U.S.-led mission to Venus, which some planetary scientists have considered “the forgotten planet.” Venus is remarkably similar to Earth in size and mass. And although it is a hellish, inhospitable world today, it may once have been a temperate, ocean-covered planet like our own. Understanding how Venus became such an extremely unfriendly world is crucial for understanding how common truly Earth-like planets might be.

“We have an Earth-size planet next door that is nothing like Earth—why? That’s a pretty important thing to figure out,” says Paul Byrne, a planetary scientist at North Carolina State University. “We have some pretty big questions to answer regarding the formation, characteristics, and evolution of an Earth-size world.”

Double the fun

NASA’s Discovery program supports smaller, less expensive missions than those in its New Frontiers and flagship categories. Launching roughly every 36 months, Discovery missions are typically capped at $450 million, excluding launch vehicle and mission operations costs, while New Frontiers expeditions are capped at $850 million. Flagships—such as the Perseverance and Curiosity Mars rovers—can cost billions.

Currently, NASA is flying two Discovery missions. The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, launched in 2009, has spent more than a decade mapping the moon’s surface. The InSight Lander, launched in 2018, is studying the Martian interior.

In 2021, two more missions will launch: Lucy will study multiple asteroids and use them to uncover secrets about the early solar system, while Psyche will visit a giant, extremely metal-rich asteroid of the same name. At the time, some scientists grumbled about two asteroid missions being selected—especially given that they beat out several proposed Venus missions, including VERITAS and DAVINCI+.

A long time coming

Now, those missions will at last have their chance to fly, exposing new truths about the shrouded world next door.

The last U.S. mission to Venus, Magellan, ended in 1994 as the spacecraft executed a programmed plunge through the planet’s atmosphere. Since then, European and Japanese probes have visited Earth’s twisted sister, and scientists have continued to aim Earth-based telescopes at the intriguing planet.

Despite the scrutiny, Venus’s mysteries have only deepened. Among them is growing evidence for ongoing volcanism on the planet’s surface, despite the fact that Venus lacks the type of tectonic activity that fuels Earth’s most extremely volcanic regions. There’s also the controversial detection of phosphine gas in the planet’s atmosphere, which could be a sign of life.

Soon, perhaps by 2030, the Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging, or DAVINCI+, spacecraft will set sail for Venus. It will then descend through the planet’s atmosphere, which is 90 times denser than Earth’s, collecting samples and relaying data that will help scientists understand how it evolved, and whether the planet ever had oceans.

While DAVINCI+ studies the Venusian shroud, the Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy, or VERITAS, spacecraft will be busy mapping the planet’s surface from orbit. Those images, plus detailed information about surface chemistry and topography, will help reconstruct Venus’s geologic history—and perhaps solve the mystery of how it evolved into the hellhole next door.

“My poor dog really thought our house was under attack from the way I was screaming when I found out our mission was selected,” tweeted the Planetary Science Institute’s David Grinspoon, a member of the DAVINCI+ team.

“I’ve been pushing for this for literally my entire career,” he also tweeted. “Last U.S. Venus mission launched in 1989, year I finished grad school. So much to learn about climate, history of Earth-like worlds & life in the universe.”

Source: National Geographic