The engineers huddled around a telemetry screen, and the mood was tense. They were watching streams of data from a crippled spacecraft more than 50 million miles away – so far that even at the speed of light, it took nearly nine minutes for a signal to travel to the spacecraft and back.

It was late August 2013, and the group of about five employees at Ball Aerospace in Boulder, Colorado, was waiting for NASA’s Kepler space telescope to reveal whether it would live or die. A severe malfunction had robbed the planet-hunting Kepler of its ability to stay pointed at a target without drifting off course.

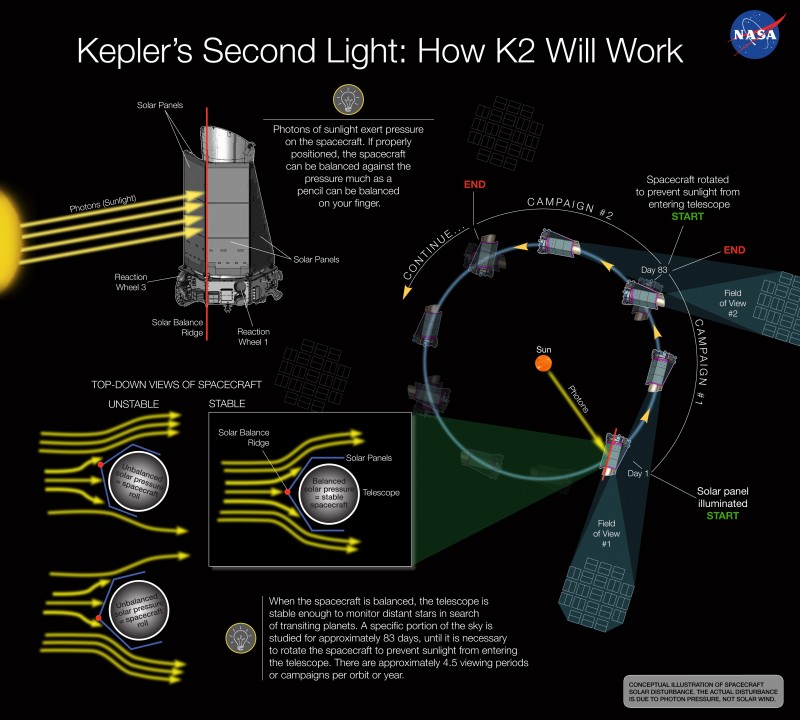

The engineers had devised a remarkable solution: using the pressure of sunlight to stabilize the spacecraft so it could continue to do science. Now, there was nothing more they could do but wait for the spacecraft to reveal its fate.

“You’re not watching it unfold in real time,” said Dustin Putnam, Ball’s attitude control lead for Kepler. “You’re watching it as it unfolded a few minutes ago, because of the time the data takes to get back from the spacecraft.”

Finally, the team received the confirmation from the spacecraft they had been waiting for. The room broke out in cheers. The fix worked! Kepler, with a new lease on life, was given a new mission as K2. But the biggest surprise was yet to come. A space telescope with a distinguished history of discovering distant exoplanets – planets orbiting other stars – was about to outdo even itself, racking up hundreds more discoveries and helping to usher in entirely new opportunities in astrophysics research.

“Many of us believed that the spacecraft would be saved, but this was perhaps more blind faith than insight,” said Tom Barclay, senior research scientist and director of the Kepler and K2 guest observer office at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California's Silicon Valley. "The Ball team devised an ingenious solution allowing the Kepler space telescope to shine again."

The discoveries roll in

A little more than two years after the tense moment for the Ball engineers, K2 has delivered on its promise with a breadth of discoveries. Continuing the exoplanet-hunting legacy, K2 has discovered more than three dozen exoplanets and with more than 250 candidates awaiting confirmation. A handful of these worlds are near-Earth-sized and orbit stars that are bright and relatively nearby compared with Kepler discoveries, allowing scientists to perform follow-up studies. In fact, these exoplanets are likely future targets for the Hubble Space Telescope and the forthcoming James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), with the potential to study these planets’ atmospheres in search of signatures indicative of life.

|

|

In this artist’s conception, a tiny rocky object vaporizes as it orbits a white dwarf star. Astronomers have detected the first planetary object transiting a white dwarf using data from the K2 mission. Slowly the object will disintegrate, leaving a dusting of metals on the surface of the star.

Credits: CfA/Mark A. Garlick

|

K2 also has astronomers rethinking long-held planetary formation theory, and the commonly understood lonely "hot Jupiter" paradigm. The unexpected discovery of a star with a close-in Jupiter-sized planet sandwiched between two smaller companion planets now has theorists back at their computers reworking the models, and has sent astronomers back to their telescopes in search of other hot Jupiter companions.

“It remains a mystery how a giant planet can form far out and migrate inward leaving havoc in its wake and still have nearby planetary companions,” said Barclay.

Like its predecessor, K2 searches for planetary transits – the tiny, telltale dip in the brightness of a star as a planet crosses in front – and for the first time caught the rubble from a destroyed exoplanet transiting across the remains of a dead star known as a white dwarf. Exoplanets have long been thought to orbit these remnant stars, but not until K2 has the theory been confirmed.

K2 has fixed its gaze on regions of the sky with densely packed clusters of stars which has revealed the first transiting exoplanet in such an area, popularly known as the Hyades star cluster. Clusters are exciting places to find exoplanets because stars in a cluster all form around the same time, giving them all the same "born-on" date. This helps scientists understand the evolution of planetary systems.

The repurposed spacecraft boasts discoveries beyond the realm of exoplanets. Mature stars – about the age of our sun and older – largely populated the original single Kepler field of view. In contrast, many K2 fields see stars still in the process of forming. In these early days, planets also are assembled and by looking at the timescales of star formation, scientists gain insight into how our own planet formed.

Studies of one star-forming region, called Upper Scorpius, compared the size of young stars observed by K2 with computational models. The result demonstrated fundamental imperfections in the models. While the reason for these discrepancies is still under debate, it likely shows that magnetic fields in stars do not arise as researchers expect.

Looking in the ecliptic – the orbital path traveled around the sun by the planets of our solar system and the location of the zodiac – K2 also is well equipped to observe small bodies within our own solar system such as comets, asteroids, dwarf planets, ice giants and moons. Last year, for instance, K2 observed Neptune in a dance with its two moons, Triton and Nereid. This was followed by observations of Pluto and Uranus.

|

Seventy days worth of solar system observations from K2 are highlighted in this sped-up movie. Neptune, in a dance with its moons, demonstrates the solar system in action. Neptune appears on day 15, followed by its moon Triton, which looks small and faint. Keen-eyed observers can also spot Neptune's tiny moon Nereid at day 24.

|

“K2 can’t help but observe the dynamics of our planetary system, " said Barclay. "We all know that planets follow laws of motion but with K2 we can see it happen.”

These initial accomplishments have come in the first year and a half since K2 began in May 2014, and have been carried off without a hitch. The spacecraft continues to perform nominally.

Searching for far out worlds

In April, K2 will take part in a global experiment in exoplanet observation with a special observing period or campaign, Campaign 9. In this campaign, both K2 and astronomers at ground-based observatories on five continents will simultaneously monitor the same region of sky towards the center of our galaxy to search for small planets, such as the size of Earth, orbiting very far from their host star or, in some cases, orbiting no star at all.

For this experiment, scientists will use gravitational microlensing – the phenomenon that occurs when the gravity of a foreground object, such as a planet, focuses and magnifies the light from a distant background star. This detection method will allow scientists to find and determine the mass of planets that orbit at great distances, like Jupiter and Neptune do our sun.

Design by community

What could turn out to be one of the most important legacies of K2 has little to do with the mechanics of the telescope, now operating on two wheels and with an assist from the sun.

The Kepler mission was organized along traditional lines of scientific discovery: a targeted set of objectives carefully chosen by the science team to answer a specific question on behalf of NASA – how common or rare are "Earths" around other suns?

K2’s modified mission involves a whole new approach-- engaging the scientific community at large and opening up the spacecraft's capabilities to a broader audience.

"The new approach of letting the community decide the most compelling science targets we’re going to look at has been one of the most exciting aspects," said Steve Howell, the Kepler and K2 project scientist at Ames. "Because of that, the breadth of our science is vast, including star clusters, young stars, supernovae, white dwarfs, very bright stars, active galaxies and, of course, exoplanets.”

In the new paradigm, the K2 team laid out some broad scientific objectives for the mission and planned to operate the spacecraft on behalf of the community.

Kepler’s field of view surveyed just one patch of sky in the northern hemisphere. The K2 ecliptic field of view provides greater opportunities for Earth-based observatories in both the northern and southern hemispheres, allowing the whole world to participate.

With more than two years of fuel remaining, the spacecraft’s scientific future continues to look unexpectedly bright.

Ames manages the Kepler and K2 missions for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, managed Kepler mission development. Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corporation operates the flight system with support from the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

For more information about the Kepler and K2 missions, visit: