On isolated mountaintops across the planet, scientists await word that tonight is the night: The complex coordination between dozens of telescopes on the ground and in space is complete, the weather is clear, tech issues have been addressed—the metaphorical stars are aligned. It is time to look at the supermassive black hole at the heart of our Milky Way galaxy.

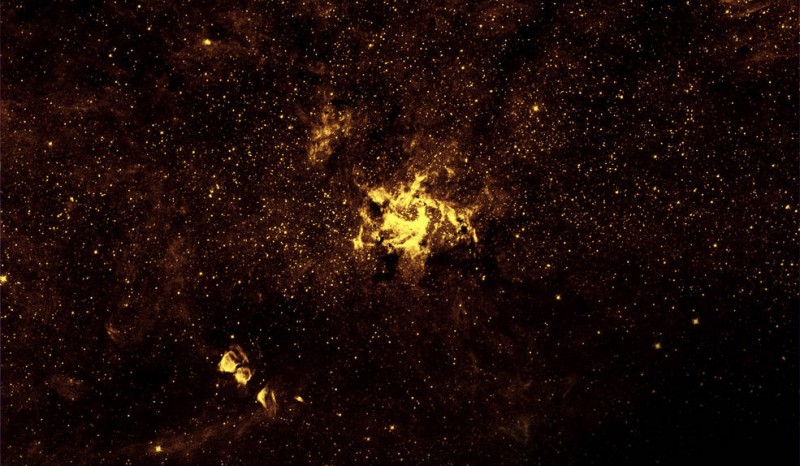

An enormous swirling vortex of hot gas glows with infrared light, marking the approximate location of the supermassive black hole at the heart of our Milky Way galaxy. This multiwavelength composite image includes near-infrared light captured by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, and was the sharpest infrared image ever made of the galactic center region when it was released in 2009. Dynamic flickering flares in the region immediately surrounding the black hole, named Sagittarius A*, have complicated the efforts of the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) collaboration to create a closer, more detailed image. While the black hole itself does not emit light and so cannot be detected by a telescope, the EHT team is working to capture it by getting a clear image of the hot glowing gas and dust directly surrounding it. NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled to launch in December 2021, will combine Hubble’s resolution with even more infrared light detection. In its first year of science operations, Webb will join with EHT in observing Sagittarius A*, lending its infrared data for comparison to EHT’s radio data, making it easier to determine when bright flares are present, producing a sharper overall image of the region. In the composite image shown here, colors represent different wavelengths of light. Hubble’s near-infrared observations are shown in yellow, revealing hundreds of thousands of stars, stellar nurseries, and heated gas. The deeper infrared observations of NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope are shown in red, revealing even more stars and gas clouds. Light detected by NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory is shown in blue and violet, indicating where gas is heated to millions of degrees by stellar explosions and by outflows from the supermassive black hole.

This “scheduling Sudoku,” as the astronomers call it, happens each day of an observing campaign by the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) collaboration, and they will soon have a new player to factor in; NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope will be joining the effort. During Webb’s first slate of observations, astronomers will use its infrared imaging power to address some of the unique and persistent challenges presented by the Milky Way’s black hole, named Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*; the asterisk is pronounced as “star”).

In 2017, EHT used the combined imaging power of eight radio telescope facilities across the planet to capture the historic first view of the region immediately surrounding a supermassive black hole, in the galaxy M87. Sgr A* is closer but dimmer than M87’s black hole, and unique flickering flares in the material surrounding it alter the pattern of light on an hourly basis, presenting challenges for astronomers.

“Our galaxy’s supermassive black hole is the only one known to have this kind of flaring, and while that has made capturing an image of the region very difficult, it also makes Sagittarius A* even more scientifically interesting,” said astronomer Farhad Yusef-Zadeh, a professor at Northwestern University and principal investigator on the Webb program to observe Sgr A*.

The flares are due to the temporary but intense acceleration of particles around the black hole to much higher energies, with corresponding light emission. A huge advantage to observing Sgr A* with Webb is the capability of capturing data in two infrared wavelengths (F210M and F480M) simultaneously and continuously, from the telescope’s location beyond the Moon. Webb will have an uninterrupted view, observing cycles of flaring and calm that the EHT team can use for reference with their own data, resulting in a cleaner image.

The source or mechanism that causes Sgr A*’s flares is highly debated. Answers as to how Sgr A*’s flares begin, peak, and dissipate could have far-reaching implications for the future study of black holes, as well as particle and plasma physics, and even flares from the Sun.

“Black holes are just cool,” said Sera Markoff, an astronomer on the Webb Sgr A* research team and currently vice chairperson of EHT’s Science Council. “The reason that scientists and space agencies across the world put so much effort into studying black holes is because they are the most extreme environments in the known universe, where we can put our fundamental theories, like general relativity, to a practical test.”

Heated gas swirls around the region of the Milky Way galaxy’s supermassive black hole, illuminated in near-infrared light captured by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. Released in 2009 to celebrate the International Year of Astronomy, this was the sharpest infrared image ever made of the galactic center region. NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled to launch in December 2021, will continue this research, pairing Hubble-strength resolution with even more infrared-detecting capability. Of particular interest for astronomers will be Webb’s observations of flares in the area, which have not been observed around any other supermassive black hole and the cause of which is unknown. The flares have complicated the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) collaboration’s quest to capture an image of the area immediately surrounding the black hole, and Webb’s infrared data is expected to help greatly in producing a clean image.

Black holes, predicted by Albert Einstein as part of his general theory of relativity, are in a sense the opposite of what their name implies—rather than an empty hole in space, black holes are the most dense, tightly-packed regions of matter known. A black hole’s gravitational field is so strong that it warps the fabric of space around itself, and any material that gets too close is bound there forever, along with any light the material emits. This is why black holes appear “black.” Any light detected by telescopes is not actually from the black hole itself, but the area surrounding it. Scientists call the ultimate inner edge of that light the event horizon, which is where the EHT collaboration gets its name.

The EHT image of M87 was the first direct visual proof that Einstein’s black hole prediction was correct. Black holes continue to be a proving ground for Einstein’s theory, and scientists hope carefully scheduled multi-wavelength observations of Sgr A* by EHT, Webb, X-ray, and other observatories will narrow the margin of error on general relativity calculations, or perhaps point to new realms of physics we don’t currently understand.

As exciting as the prospect of new understanding and/or new physics may be, both Markoff and Zadeh noted that this is only the beginning. “It’s a process. We will likely have more questions than answers at first,” Markoff said. The Sgr A* research team plans to apply for more time with Webb in future years, to witness additional flaring events and build up a knowledge base, determining patterns from seemingly random flares. Knowledge gained from studying Sgr A* will then be applied to other black holes, to learn what is fundamental to their nature versus what makes one black hole unique.

So the stressful scheduling Sudoku will continue for some time, but the astronomers agree it’s worth the effort. “It’s the noblest thing humans can do, searching for truth,” Zadeh said. “It’s in our nature. We want to know how the universe works, because we are part of the universe. Black holes could hold clues to some of these big questions.”

NASA’s Webb telescope will serve as the premier space science observatory for the next decade and explore every phase of cosmic history—from within our solar system to the most distant observable galaxies in the early universe, and everything in between. Webb will reveal new and unexpected discoveries, and help humanity understand the origins of the universe and our place in it. Webb is an international program led by NASA with its partners, ESA (European Space Agency) and the Canadian Space Agency.

Source: NASA