When a moon passes in front of a star — also known an occultation — it temporarily blocks the star's light, giving researchers a unique opportunity to study the profile of the object in the foreground.

On Oct. 5, 2017, Triton passed in front of a distant star called UCAC4 410-143659, which is in the constellation of Aquarius. Using data from the Gaia spacecraft, the researchers were able to narrow down the best locations to observe this rare occultation and learn more about Triton. [Neptune's Biggest (but Odd) Moon: Triton]

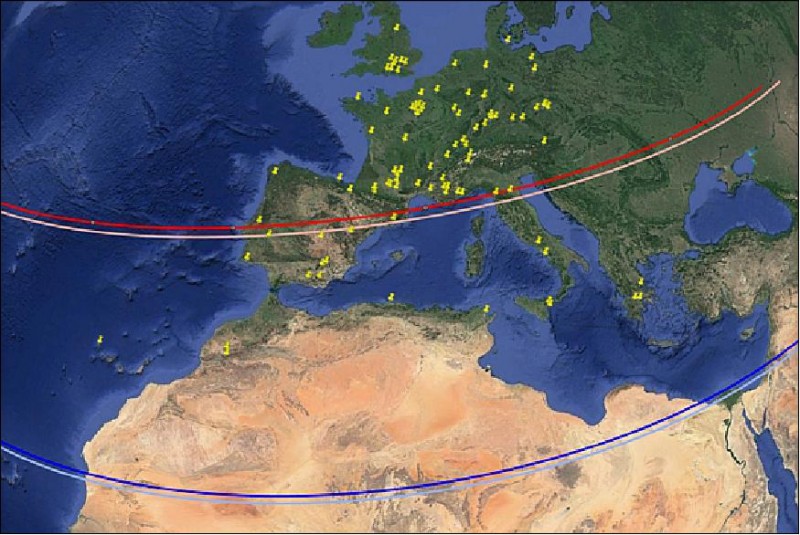

The Gaia spacecraft is used to make precise measurements of the positions of more than a billion stars. In this case, the researchers wanted to pinpoint the specific path that the moon's shadow would follow as it swept across our planet. Previous observations showed that within less than 3 minutes, the occultation would first cross Europe and North Africa, before moving toward North America, according to a statement from the European Space Agency (ESA).

Scientists used measurements from the Gaia spacecraft to predict where on Earth it was best to watch Neptune's moon Triton pass in front of a distant star.

Somewhere within the path of the moon's shadow, which was a couple of thousand kilometers wide, was an even narrower 62-mile-wide (100 km) strip where viewers had the opportunity to see what is called a "central flash" halfway through the occultation. The central flash occurs when starlight filters through Triton's atmosphere, giving researchers a rare opportunity to learn more about its makeup and any potential haze. The researchers used data from the Gaia spacecraft to locate the best locations to observe the occultation, and possibly the central flash, according to the statement.

"This occultation was a rare opportunity to detect possible changes in Triton's atmospheric pressure," ESA officials said in the statement. "Observations of the central flash can also provide unique information to detect possible winds near Triton's surface; current analysis of the data indicates a quiet and still atmosphere."

In preparation for Triton's occultation, the researchers used Gaia data released in 2016, which revealed the position of the star UCAC4 410-143659. However, to learn more about the star's proper motion, or how it moves across the sky, the researchers contacted the Gaia team, who provided additional information ahead of publishing the second batch of data on April 25, 2018.

Not only did this data include information about the preliminary position and proper motion of the occulted star, but it also showed the positions of 453 other stars, which helped to further refine the estimate of Triton's orbit and the location of the central flash, according to the statement.

In fact, "with this additional information, they computed again the location of the thin strip where the central flash would be observed, shifting it roughly 300 km southwards of the earlier prediction," ESA officials said in the statement.

With the help of Gaia, observers were able to closely monitor the phenomenon on Oct. 5, 2017, and detect the central flash. Astronomers are now studying the data collected during occultation to learn more about the atmosphere of Triton. The researchers plan to use Gaia for future observations of other stellar occultations, including the passing of Triton in front of another star on Oct. 6, 2022.

Source: Samantha Mathewson