Some sky phenomena are fairly common but rarely noticed because of their supposed difficulty or appearance at odd hours. Like the planet Mercury: Once you know when and where to look, it’s easy to find it at dusk or dawn multiple times each year.

I've found the same is true for the green flash, a brief but colorful atmospheric phenomenon that occurs at the moment of sunrise and sunset. For a second or two, the Sun’s upper rim can appear intensely green. Although called a “flash,” it's more a vividly green coloration to the first or last blip of the Sun visible at the horizon.

A friend of mine saw the flash for the first time while watching a sunset along the north shore of Lake Superior. He wasn’t even looking for it, but when it was over a second later, he turned to his paddling partner and asked “Did we just see the green flash?” Yes, they did! My first sighting was through a camera viewfinder, and I was equally surprised.

A mirage at sunrise on April 22nd caused this snippet of green flash to separate from the Sun before shrinking and disappearing. Mirages often enhance the phenomenon.

Bob King

To read about it, the flash would seem as rare a sight as a Venus transit, but this spring I discovered otherwise. You don't need perfect skies (a little haze or cloud is OK) or a tropical ocean, but you willneed to be able to see down to within ½° or one full Moon diameter of the true horizon.

Most photos of the phenomenon are taken over the ocean or other large bodies of water, but there's no reason why it can't be seen over land provided the horizon is flat and distant. Mountaintops with a clear view across the plains should do the trick or even the flatlands of central Illinois, Kansas, and Nebraska.

While some haze is inevitable near the horizon, the sky doesn't have to be perfect. But if the Sun looks like a cherry-red ball, say from fire haze, you can safely cancel your green flash session. Best viewing occurs when the Sun remains yellow-orange toward the horizon and too bright for a quick glance.

The green flash didn’t get much attention from skywatchers until Jules Verne mentioned it in his novel Le Rayon Vert (The Green Ray). Verne wrote ecstatically about the color of the flash as “a most wonderful green, a green which no artist could obtain on his palette, a green of which neither the varied tints of vegetation nor the shades of the most limpid sea could ever produce the like! If there is a green in Paradise, it cannot but be of this shade, which most surely is the true green of Hope.”

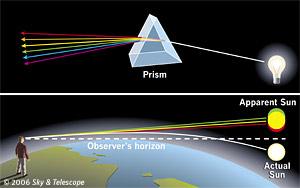

Green flashes occur because the atmosphere refracts, or bends, light from the Sun, especially when it's near the horizon, where our line of sight traverses hundreds of miles of the lower atmosphere. Air is denser there and particularly so when our line of sight grazes the horizon.

Air can act just like a prism to spread sunlight into its component colors. The degree to which light beams refract depends on their color (wavelength). Refraction is strongest when the Sun lies low above the horizon, creating a blue-green fringe on the top edge of its disk and a red fringe below.

A prism spreads sunlight into a rainbow of colors according to wavelength, from blue at one end to red at the other. Different colors of light are refracted by different amounts because they travel at slightly different speeds through the glass. Short wavelength violet travels slowest and suffers the strongest refraction compared to red light, which is refracted least.

Dense air near the horizon acts as it own prism and spreads sunlight into a rainbow of closely overlapping images of the solar disk, each a different color from violet to red. The spreading of light according to color is called dispersion, and it’s small enough that most of those images overlap and produce white light . . . except at the very top and bottom of the solar disk. Blue and green, the most strongly refracted colors, stand highest above the horizon and fringe the Sun's top edge blue-green. Red, the least bent, forms a red fringe at the bottom.

Dispersion of light by atmospheric refraction near the horizon gives the rising Moon a green fringe at top and red fringe at bottom (left). The diagram at right illustrates how refraction spreads the Sun into multiple overlapping disks with the blue-green and red ones peeping out at top and bottom.

Bob King

Even a gibbous or full Moon will show dispersion when near the horizon. While challenging to see with the naked eye, binoculars will easily show the full Moon’s greenish-blue upper edge and reddish-purple bottom when viewed with minutes of moonrise. Try it out during the full Strawberry Moon on June 27–28.

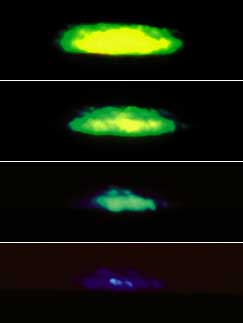

On rare instances of extremely clear skies, the Sun may produce a blue flash. This sequence was captured in Finland. The same situation can happen in reverse at sunrise, but to see it you’ll have to determine exactly where and when the Sun will rise.

Pekka Parviainen

Since blue light is bent more than green light, why doesn’t the Sun’s edge look blue instead? Why not a blue flash? Blue light gets scattered away from the Sun by air molecules and lends its color to the blue sky, so it's generally not a player at sunset and sunrise. Rarely, under the clearest conditions, violet flashes have been recorded. I've seen just one blue-violet flash but more than a handful of green flashes in nearly as many sunrises this spring.

Because of obstructions in the western direction, nearly all my green flash sightings have been at sunrise over Lake Superior. Sunrises are a touch more challenging for viewing the flash than sunsets because you have to anticipate where the Sun will rise; at sunset you can see exactly where the last bit of Sun will set.

That said, it's pretty easy in practice. I get up a half hour before sunup, drive to an overlook, and focus my attention on the bright spot along the eastern horizon where the Sun will rise. Then I just have to wait for that glorious little bead of emerald green to pop. You can't miss it. The color is so vibrant and unexpected it can take your breath away. For sunset watchers, the flash appears as a last dab of lingering light as the solar disk drops out of sight.

Watch the green flash appear several times in this real-time video of a sunset.

With clear skies and a good horizon, there’s no reason why the flash can’t be seen routinely. You need only keep your eye on the weather and show up. Take care to avoid looking directly at the solar disk because of potential damage to your eyesight. You'll also momentarily dazzle your retinas and end up trying to blink away afterimages obscuring your field of vision. Save your eyes for the last smidge of sunset or sunset, when it’s safe to look.

Witness the green flash on Cerro Paranal, the 2600-meter-high mountain that's home to the ESO’s Very Large Telescope in Chile’s Atacama Desert .

G.Hüdepohl (atacamaphoto.com) / ESO

Does the Moon also produce green flashes? While probably too faint to see with the unaided eye, lunar green flashes from the rising gibbous or full Moon have been seen in binoculars and recorded on camera. The same viewing rules apply: You need generally clear air, a distant and flat horizon, and to know just where to anticipate the moonrise. This link will provide moonrise and moonset times for your location; this one will give you the times of sunrise and sunset.

This sequence of photos shows the development of the green flash aided by temperature differences in the air layers that created strange distortions of the Sun's shape.

Mila Zincova / CC BY-SA 3.0

Mirages are common over large land surfaces and bodies of water, and they can make the green flash easier to see. An inferior mirage, better known as the “hot road” mirage, can isolate and expand the Sun’s green upper rim into a distinct patch of green light that appears to hover a second or two above the departing or rising Sun before evaporating into thin air.

Nature offers mesmerizing sights like the green flash for only a little effort. Go out and see for yourself what so excited Jules Verne that he was compelled to write a love story with the green flash as its central theme.