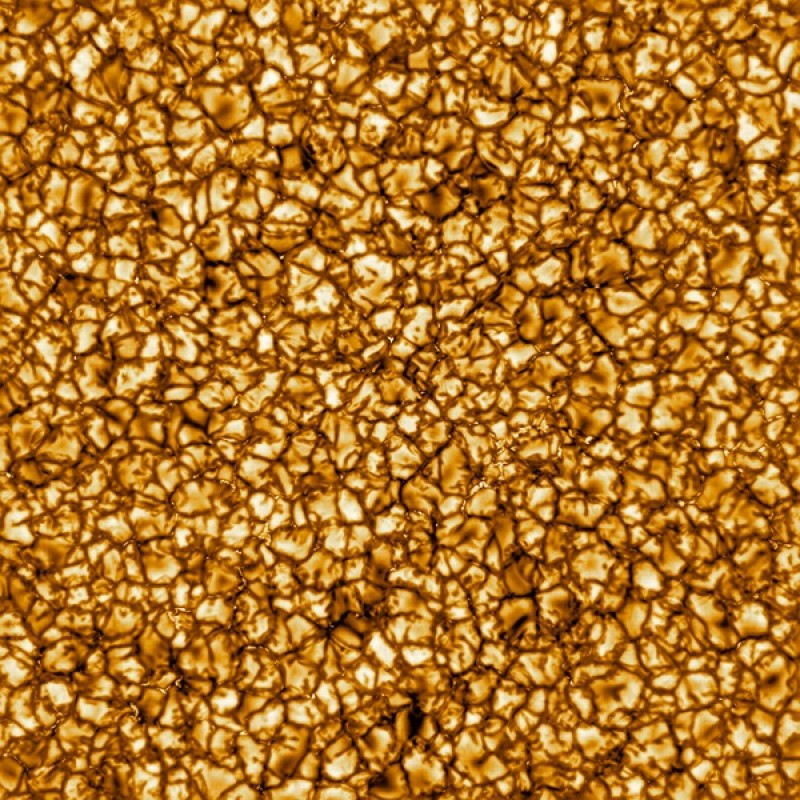

Bubbling convection cells, each about the size of Texas, rise and fall across the Sun's surface.

A new solar telescope in Hawaii has taken its first photo and movie of the Sun. The shots are the highest resolution views of our star yet, showing details on the Sun’s surface as small as about 18 miles in size.

The Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope is located on the Haleakala volcano on the island of Maui. A primary mirror that's 4 meters (about 13 feet) wide makes this the biggest solar telescope on Earth, and it will be able to resolve smaller details on the Sun than ever before. With the telescope’s sophisticated instruments and high resolution, scientists hope to better understand remaining mysteries about our nearest star.

The hotter parts where new plasma has just risen up from below appear bright in the photo, while the places where cooler plasma sinks back down appear dark. The grains in this first image from the telescope are roughly the size of Texas.

The bubbling motions of hot plasma in the Sun are tied to some of the greatest remaining mysteries about our star. Because plasma is electrically charged, its motions can create magnetic fields. The Sun’s magnetic fields are responsible for a lot of its most dynamic behavior, like solar storms that can disrupt satellites and power grids on Earth.

“Most solar storms originate in places on the Sun where there’s strong magnetism, strong concentrations of magnetic forces,” Rebecca Centano Elliott, a solar scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, tells Astronomy.

Many of the telescope’s instruments are well suited to studying magnetic fields because they can measure properties of light beyond brightness and color that carry information about magnetic forces in the Sun’s atmosphere.

Additionally, the telescope’s ability to capture more minute details on the Sun’s surface than ever before will help scientists test theories about the Sun’s workings that eluded previous observations.

“This is a huge leap for our field, I think, in terms of observations,” says Centano Elliott.

The Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope is located on the Haleakala volcano on the island of Maui. A primary mirror that's 4 meters (about 13 feet) wide makes this the biggest solar telescope on Earth, and it will be able to resolve smaller details on the Sun than ever before. With the telescope’s sophisticated instruments and high resolution, scientists hope to better understand remaining mysteries about our nearest star.

A bubbling star

The grainy pattern in the telescope’s “first light” image is the mark of plasma cells on the Sun’s surface. Hot plasma from within the Sun rises to the surface, cools and sinks back down in a process called convection, like bubbling water in a boiling pot.The hotter parts where new plasma has just risen up from below appear bright in the photo, while the places where cooler plasma sinks back down appear dark. The grains in this first image from the telescope are roughly the size of Texas.

The bubbling motions of hot plasma in the Sun are tied to some of the greatest remaining mysteries about our star. Because plasma is electrically charged, its motions can create magnetic fields. The Sun’s magnetic fields are responsible for a lot of its most dynamic behavior, like solar storms that can disrupt satellites and power grids on Earth.

“Most solar storms originate in places on the Sun where there’s strong magnetism, strong concentrations of magnetic forces,” Rebecca Centano Elliott, a solar scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, tells Astronomy.

Magnetic mysteries

Being able to better understand and monitor magnetic fields on the Sun could let researchers better predict when potentially dangerous solar storms will occur.Many of the telescope’s instruments are well suited to studying magnetic fields because they can measure properties of light beyond brightness and color that carry information about magnetic forces in the Sun’s atmosphere.

Additionally, the telescope’s ability to capture more minute details on the Sun’s surface than ever before will help scientists test theories about the Sun’s workings that eluded previous observations.

“This is a huge leap for our field, I think, in terms of observations,” says Centano Elliott.