Catch a conjunction of Mars and Mercury and see Jupiter at its best from August 13 to 20.

King of the planets: The solar system’s largest planet, mighty Jupiter, reaches opposition this week. It’s the best time to turn your gaze toward the planet and its moons.

Friday, August 13

Although the Perseids peaked yesterday, today is still a great time to catch some of the shower’s plentiful shooting stars. In fact, the Perseids are often considered one of the year’s best meteor showers and, depending on the time and location you step outside to take in the sky, you can expect to see somewhere between about 20 and 90 meteors per hour.

If you do plan to catch the show tonight, wait until the Moon has set (or nearly set) to reduce background light. Choose a comfortable, dark viewing location and look northeast, where the constellation Perseus is rising. The constellation’s brightest star is magnitude 1.8 Mirfak, and the Perseids’ radiant sits about 8° to the upper left (northwest) of this star as they rise. The radiant is much closer — 0.7° north-northwest — to magnitude 4.8 Lambda (λ) Persei.

With the constellation low to the horizon, you’re looking through a significant slice of Earth’s atmosphere and the rate of meteors you’ll see will be lower — closer to 20 per hour. The longer you wait (and as midnight comes and goes, carrying you into August 14), the higher the constellation and the radiant will rise, and so will the number of meteors you see.

While you’re studying this region of sky, turn your gaze to Algol, Perseus’ beta star. This star is actually a special type of binary system called an eclipsing binary, in which one star passes in front of the other from our viewpoint here on Earth. As a result, every 2.867 days, Algol appears to dim from magnitude 2.1 to magnitude 3.4, or 30 percent its normal brightness. The entire process takes just a few hours. When uneclipsed, Algol is comparable in brightness to Mirfak. While hidden by its companion, however, Algol is noticeably dimmer. Which is it tonight?

Sunrise: 6:10 A.M.

Sunset: 7:59 P.M.

Moonrise: 11:35 A.M.

Moonset: 11:00 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (29%)

*Times for sunrise, sunset, moonrise, and moonset are given in local time from 40° N 90° W. The Moon’s illumination is given at 12 P.M. local time from the same location.

Saturday, August 14

The Butterfly Cluster M6 in Scorpius: M6, also called the Butterfly Cluster, is a young group of stars sporting a distinctly orange spot: the variable star BM Scorpii.

Look to the southern sky this evening to explore the central regions of our Milky Way, whose core falls near the Teapot’s spout in Sagittarius. The waxing Moon is nearby in Libra, potentially washing out the Milky Way’s disk even from slightly darker locations, but there’s still plenty to be seen here, as this is a region rich with star clusters.

Several sit in the domain of Scorpius, who lies west of Sagittarius in the sky. Two are M6 and M7, which sit just above the stinger at the end of the Scorpion’s tail. First find magnitude 1.6 Shaula (Lambda [λ] Scorpii); just to this star’s lower right (southwest) is magnitude 2.7 Lesath (Upsilon [υ] Scorpii). Together, these two stars make up the tail’s stinger. They are sometimes called the Cat’s Eyes.

Draw a line from Lesath to Shaula, then continue that line about 4.5° in the same direction. You’ll run smack dab into M7, an open cluster also known as Ptolemy’s Cluster. With a visual magnitude of about 3, it should be visible to the naked eye under dark skies. If not, binoculars or any size telescope will bring it out. This cluster sports roughly 80 stars brighter than magnitude 10 within about 1.3° of the sky. These stars are all young suns recently born within the last 220 million years or so.

Next, it’s a short journey to M6, which lies a little less than 4° north-northwest of M7. Like its neighbor, M6 is a young open cluster that’s just a little fainter at magnitude 4. It is sometimes called the Butterfly Cluster, as its stars resemble a butterfly with its wings outspread. This cluster is even younger — around 100 million years — and its brightest star, HD 160371 (also called BM Scorpii), is a variable whose magnitude ranges from 5.5 at its brightest to 7 at its dimmest. This star is easy to pick out from its blue-hued brethren, as it is distinctly orange in color.

Sunrise: 6:11 A.M.

Sunset: 7:58 P.M.

Moonrise: 12:46 P.M.

Moonset: 11:31 PM

Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (40%)

Sunday, August 15

First Quarter Moon occurs at 11:20 A.M. EDT. This is an easy lunar phase to observe, as the Moon rises in the afternoon and doesn’t set until shortly after midnight. During this phase, the eastern portion of our satellite is illuminated, which (in the Northern Hemisphere) means that its right half is visible. This puts on display six of its large, dark maria: the Seas of Cold, Serenity, Tranquillity, Nectar, Crises, and Fertility. It was in the Sea of Tranquillity, the roughly oval-shaped dark patch beneath the more circular Sea of Serenity, that the first men landed on the Moon in July 1969. In addition to these lava-filled basins, several craters also stand out on the First Quarter Moon. The most prominent include Langrenus, Theophilus, Hercules, Aristoteles, and Atlas.

Now is also a great time to study the Moon’s terminator, or the line between lunar night and day. This is where contrast is often sharpest and where details truly stand out. If you observe the Moon for long stretches of time, you may even see the shadows change as daylight creeps across our satellite. Whether you have binoculars, a telescope, or no equipment at all, the Moon is an excellent target for all observers to enjoy.

Sunrise: 6:12 A.M.

Sunset: 7:56 P.M.

Moonrise: 1:59 P.M.

Moonset: —

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (51%)

Monday, August 16

Early this morning, Jupiter’s moons will put on a special show. Mutual events in which one moon or its shadow block another are only possible when we’re viewing the giant planet at just the right angle — as we are now. Observers in the central and western portions of the U.S. should look this morning with a telescope near the border of Aquarius and Capricornus to find bright Jupiter (magnitude –2.9) still in Aquarius, about 1.5° west of magnitude 4.2 Iota (ι) Aquarii.

The planet sits in a rich starfield, with Io 1.5° to Jupiter’s east and Callisto, Ganymede, and Europa (from east to west) about 3.5' to the west. Ganymede’s large shadow falls across Europa between 5:03 A.M. and 5:35 A.M. CDT, followed by a 10-minute-long occultation as Ganymede itself blocks Europa from 5:43 A.M. to 5:53 A.M. CDT. By then, it’s twilight in the Midwest, so observers in Mountain and Pacific time zones will get the best view in the darkest sky. Note that Callisto is only 13" east of the pair.

Sunrise: 6:13 A.M.

Sunset: 7:55 P.M.

Moonrise: 3:13 P.M.

Moonset: 12:06 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (62%)

Tuesday, August 17

Omicron (ο) Ceti, better known as Mira, is a long-period variable star whose brightness waxes and wanes over a period of 332 days. This star is estimated to peak in brightness tomorrow, meaning this is a great time to enjoy its magnitude 2 to 3 glow (Mira’s peak magnitude varies somewhat) without any optical aid at all.

The best time to search out Mira and its home constellation of Cetus is early in the morning in the few hours before sunrise, when this region sits highest in the sky at this time of year. Mira is located in the central region of the constellation, a little less than halfway down a line drawn between Menkar (Alpha [α] Ceti) and Diphda (Beta [β] Ceti). At its peak, Mira should appear roughly as bright as the latter.

Over the next half a year or so, Mira will fade down to magnitude 9, disappearing from naked-eye view altogether. It will again peak in brightness in mid-July next year.

The Moon reaches perigee, the nearest point to Earth in its orbit around our planet, at 5:16 A.M. EDT. When it does, our satellite will sit 229,363 miles (369,124 kilometers) away.

Sunrise: 6:14 A.M.

Sunset: 7:54 P.M.

Moonrise: 4:24 P.M.

Moonset: 12:48 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (73%)

Wednesday, August 18

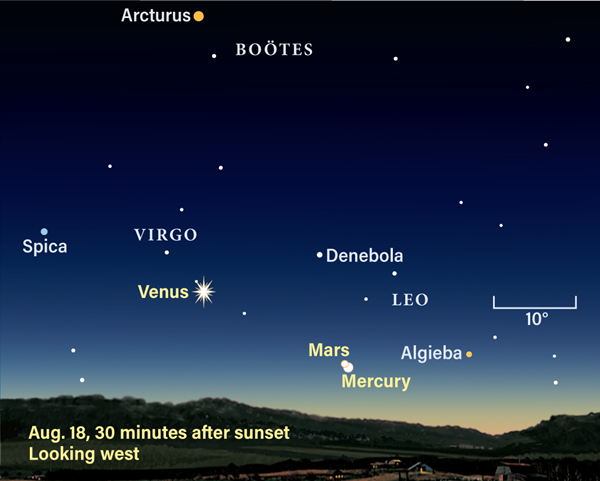

Mercury and Mars mingle: Mercury and Mars appear separated by a mere 7' shortly after sunset on Aug. 18. Use brighter Mercury as a signpost to find the dimmer Red Planet.

Mercury will pass 0.08° south of Mars at midnight EDT in a close conjunction. Neither planet is visible at that time, however, so instead, catch them just after sunset, when they are low in the west and nearly as close: about 0.1° apart. Home in on the pair with binoculars or a telescope to better see Mercury, magnitude –0.6, to the lower right (west) of Mars, magnitude 1.8. Be quick, though, as the two planets set within an hour of the Sun. (Take care to never use binoculars or a telescope while the Sun is still in the sky, as the chances for accidentally pointing them at the Sun are still high.)

20.5° farther west of the pair is brilliant Venus, blazing at magnitude –4 in Virgo. Venus remains visible for longer, finally sinking blow the horizon around 9:30 P.M. local time. It sits within 7.5° of Porrima, also known as Gamma (γ) Virginis, a beautiful binary system in which each star is roughly the mass of the Sun. These near-twin stars are separated by just over 3", with only 0.1 magnitude difference in brightness.

If you’re planning to stay up late to observe, you’ll want to set Jupiter — now located at the border between Aquarius and Capricornus) — in your sights around midnight EDT.

At that time, the Galilean moons Io and Ganymede sit just 8" from Jupiter’s western limb. Io’s shadow passes in front of and slightly dims Ganymede between 12:15 A.M. and 12:34 A.M. EDT (on the 19th; late Aug. 18 in all other U.S. time zones). Two minutes after the event ends, Io slips into Jupiter’s long, dark shadow. Ganymede follows suit, disappearing 7 minutes later.

Meanwhile, as these events are proceeding, Europa begins a transit across the disk on the planet’s eastern side at 12:37 A.M. EDT. Its shadow precedes it onto the cloud tops by 3 minutes.

Sunrise: 6:15 A.M.

Sunset: 7:52 P.M.

Moonrise: 5:30 P.M.

Moonset: 1:40 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (83%)

Thursday, August 19

Dark shadow: In 2019, the Juno spacecraft caught this stunning image of a swatch near Jupiter’s equator, showing the dark shadow of Io passing over the disk.

Jupiter reaches opposition at 8 P.M. EDT tonight. Opposition simply means that, from our viewpoint on Earth, the planet is opposite the Sun in the sky. When at opposition, a planet rises around sunset and sets around sunrise, soaring through the skies all night and offering the best, brightest look at its disk.

Tonight, Jupiter is just inside the eastern border of Capricornus, roughly 3.6° northeast of 3rd-magnitude Deneb Algedi. The planet is a bright magnitude –2.9 and warrants a closer look with binoculars or, better yet, any telescope. Jupiter has several differently colored cloud bands on display, as well as a bonus: Its Great Red Spot — a churning, Earth-sized storm — is transiting tonight. This great tempest reaches the middle of the planet’s disk at 9:24 P.M. EDT, roughly half an hour before another exciting event is set to start.

At 9:50 P.M. EDT, both Io and its shadow simultaneously slip onto the planet’s eastern side. The pair continues across the disk together, both exiting at 12:08 A.M. EDT (August 20 for those in the Eastern time zone).

While you’re in the area, there’s another solar system object at opposition today: Asteroid 43 Ariadne reached opposition at 3 A.M. EDT in Aquarius, not far from Jupiter. Swing your gaze a little less than 8° north-northwest of the giant planet to find the 10th-magnitude world, which sits 3.5° east of magnitude 2.9 Sadalsuud. Discovered in 1857, Ariadne is roughly 60 miles (95 km) across along its largest dimension.

Planet Uranus reaches its stationary point tonight in the constellation Aries at midnight EDT. The best time to find it is early in the morning, so if you’re staying up overnight, you can catch it in the hours before dawn on the 20th. It’s located in the southern part of the constellation, about 5.7° north of 4th-magnitude Mu (μ) Ceti. Binoculars should net you the magnitude 5.8 planet pretty easily.

Sunrise: 6:16 A.M.

Sunset: 7:51 P.M.

Moonrise: 6:26 P.M.

Moonset: 2:40 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (90%)

Friday, August 20

The Moon passes 4° south of Saturn at 6 P.M. EDT. By sunset a few hours later, the pair is 4.5° apart and rising in the southeast in Capricornus. Jupiter still sits nearby.

Saturn glows at magnitude 0.2 and is just two and a half weeks past its own opposition. That means it’s still ripe for viewing all night long. Zoom in on this target with a telescope to really get the most from its stunning ring system, which stretches roughly 42" across on either side of the planet’s 19"-wide disk. Saturn is surrounded by a plethora of moons, including 10th-magnitude Tethys and Dione on the planet’s eastern side and Rhea to the northwest. The planet’s brightest moon, Titan, sits much farther away: 2' east of Saturn. In the glare of Earth’s bright Moon nearby, magnitude 8 Titan may be the only one of the ringed planet’s satellites that’s easy to pick out.

Sunrise: 6:16 A.M.

Sunset: 7:49 P.M.

Moonrise: 7:14 P.M.

Moonset: 3:48 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (96%)

Source: Astronomy Magazine