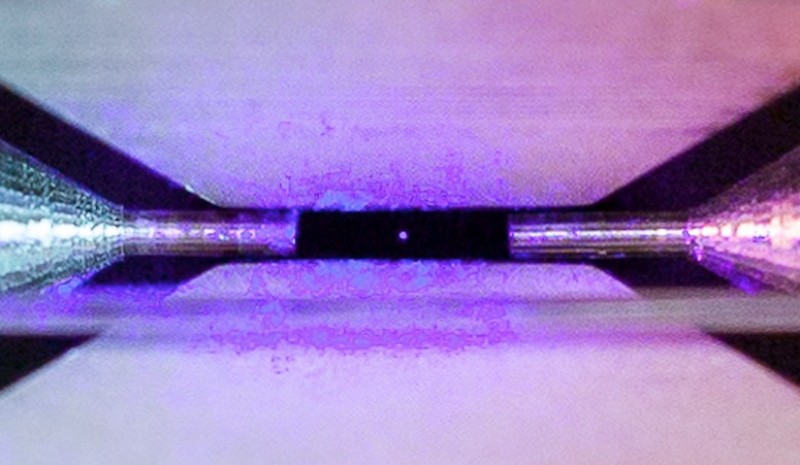

This image shows a Strontium atom held by the fields emanating from the metal electrodes surrounding it. The distance between the small needle tips is about two millimeters. Humans cannot see things that are smaller than the wavelength of the light that is reflected from the surface of an object. And Strontium has an atomic radius that is smaller than the wavelength of light. So, the question is: How can we "see" it? The answers is that we are not actually "seeing" the atom of Strontium, but rather we are seeing the light that the excited atom is giving off. (Image Credit: David Nadlinger, University of Oxford)

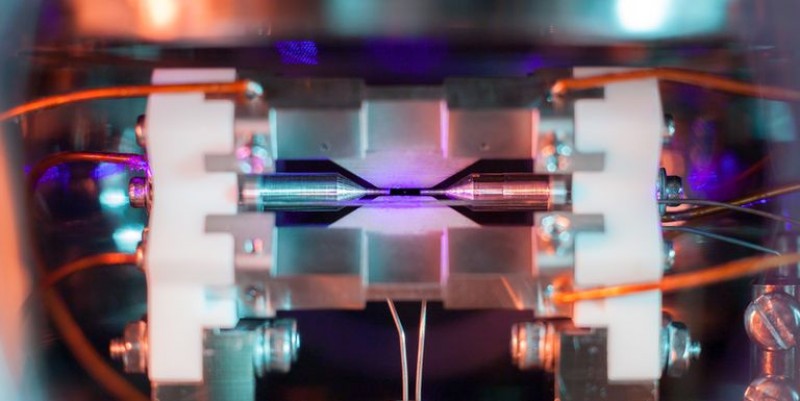

"Single Atom in an Ion Trap," by David Nadlinger, from the University of Oxford, shows the atom held by the fields emanating from the metal electrodes surrounding it. The distance between the small needle tips is about two millimeters.

When illuminated by a laser of the right blue-violet color the atom absorbs and re-emits light particles sufficiently quickly for an ordinary camera to capture it in a long exposure photograph. The winning picture was taken through a window of the ultra-high vacuum chamber that houses the ion trap.

Laser cooled atomic ions provide a pristine platform for exploring and harnessing the unique properties of quantum physics. They can serve as extremely accurate clocks and sensors or, as explored by the UK Networked Quantum Information Technologies Hub, as building blocks for future quantum computers, which could tackle problems that stymie even today's largest supercomputers.

The image, came first in the Equipment and Facilities category, as well as winning overall against many other stunning photographs featuring research in action, in the EPSRCs competition, now in its fifth year.

David Nadlinger, explained how the photograph came about: "The idea of being able to see a single atom with the naked eye had struck me as a wonderfully direct and visceral bridge between the miniscule quantum world and our macroscopic reality. A back of the envelope calculation showed the numbers to be on my side, and when I set off to the lab with camera and tripods one quiet Sunday afternoon, I was rewarded with this particular picture of a small, pale blue dot."

Professor Dame Ann Dowling said: "What I think is remarkable about the photographs submitted is that they are linked to projects supported by EPSRC and demonstrate the sheer breadth of the technical areas being funded and the opportunities for real change for people, businesses, and society through the innovations that are coming from this work."

"Not only do we have really strong, attractive photographs, [but] the stories behind them about the research and why it is being done are inspiring."

"Much of this work will lead to innovations that transform lives and, in this Year of Engineering, it's marvelous to see these great examples of transformational research."

Congratulating the winners and entrants, Professor Tom Rodden, EPSRCs Deputy Chief Executive, said: "Every year we are stunned by the quality and creativity of the entries into our competition and this year has been no exception. They show that our researchers want to tell the world about the beauty of science and engineering. I'd like to thank everyone who entered. Judging was really difficult."

"The images help the public engage with the research they fund, and I hope they will spark interest in science and engineering among people, young or older."

Dr Ellie Cosgrave said: "The winners we have selected demonstrate how science and technology is affecting people's lives today at many different physical scales. We have examples from the nano-scale, how our cells are working, how our immune systems might be able to treat different types of diseases, all the way up to technologies that can help us move through cities."

The Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC)is the main funding agency for engineering and physical sciences research in the UK. Their vision is for the UK to be the best place in the world to Research, Discover, and Innovate.

By investing 800 million Pounds a year in research and postgraduate training, EPSRC is building the knowledge and skills base needed to address the scientific and technological challenges facing the UK. Their portfolio covers a vast range of fields from healthcare technologies to structural engineering, manufacturing to mathematics, advanced materials to chemistry. The research EPSRC funds has impact across all sectors. It provides a platform for future economic development in the UK and improvements for everyone's health, lifestyle, and culture.

For clarification, please note that Strontium has an atomic radius of 215 pico-meters or 2.15x10^-10 meters. Humans cannot see things that are smaller than the wavelength of the light that is reflected from the surface of an object. The shortest wavelength of light that humans can see is about 400 nano-meters or 4x10^-7 meters.

So, the question is: How can we "see" an object that is smaller than the wavelength of light?

The answers is that we are not actually "seeing" the atom of Strontium, but rather we are seeing the light that the excited atom is giving off. The actual atom cannot be resolved by the human eye.

It's just like when you go outside at night and look at a star, you can "see" the star, but it only looks like a single point of light because it is so far away that its angular size is essentially zero. You can see the light from the star, but the human eye cannot resolve it.

The opposite is happening here, the atom is so bright that you can see the light from the atom, even though the atom itself is too small to actually see.

Source: Guy Pirro