A Full Harvest Moon hangs low in the sky above fields in Nebraska.

For those in the Northern Hemisphere, the autumnal equinox marks the start of fall. This year, the equinox falls on Wednesday, September 22 at 3:21 P.M. EDT. At that time, the Sun will cross the celestial equator — the projection of Earth’s equator out into space in all directions — heading from north to south.

The Full Moon that occurs closest to the autumnal equinox has a special name: the Harvest Moon. This year, the Harvest Moon falls just a few days before the equinox, on Monday, September 20, at 7:55 P.M. EDT. And because of some nifty celestial geometry, it brings with it a special effect called, appropriately, the Harvest Moon effect.

What is the Harvest Moon effect? Put simply, it’s a span of several days during which the Full (or nearly Full) Moon rises at almost the same time each night. This means several nights in a row receive lots of bright moonlight — a boon to farmers working hard to bring in the harvest before the advent of artificial lights.

What causes the Harvest Moon effect?

Okay, so what’s really going on? As the Moon circles Earth, we see its changing phases as the amount of illumination it receives from the Sun also changes. When it is Full, it sits directly opposite the Sun, rising around sunset and setting around sunrise. On any two successive nights, moonrise generally varies by about 50 minutes as our satellite goes from New to Full and New again. Then the cycle repeats.

But that 50-minute change from day to day is only an average. And it’s related to the angle of the Moon’s orbit with respect to Earth’s equator — because unlike many satellites in the solar system, our Moon doesn’t orbit Earth’s equator. Around the vernal equinox, which kicks off spring in the Northern Hemisphere, that interval can stretch to a 70-minute change in moonrise times from night to night. And around the autumnal equinox, it shrinks to just 20 minutes or so. (Note that these times and dates are flipped for the Southern Hemisphere, which gets the most moonlight around the vernal equinox and the least around the autumnal equinox.)

This sequence shows the Harvest Moon rising. The three 1/100-second exposures were taken 10 minutes apart on September 29, 2012, from Cosby, Missouri.

What’s happening now is the Moon is rising further north each day, which translates to — for those north of the equator at this time of year — smaller changes in the time of moonrise from day to day. That’s because the Moon’s orbit is tilted the smallest amount to the horizon or, put another way, appears most parallel with the horizon at this time.

Your latitude above or below the equator affects the magnitude of the Harvest Moon effect. This week, the farther north you live, the bigger the effect, and the closer together subsequent moonrises appear, and for longer. For example, check out the moonrise times listed below in Chicago, Illinois (at 42° N), compared with those in Fairbanks, Alaska (65° N) over the next week. In Chicago, the Moon will rise a maximum of just 22 minutes later each day for about three days in a row. But in Fairbanks, where the Moon rises earlier each day, subsequent moonrises are just 6 minutes apart for most of the week.

Local Time of Moonrise

Friday, September 17

- Chicago: 5:47 P.M.

- Fairbanks: 8:54 P.M.

Saturday, September 18

- Chicago: 6:18 P.M.

- Fairbanks: 8:46 P.M.

Sunday, September 19

- Chicago: 6:46 P.M.

- Fairbanks: 8:40 P.M.

Monday, September 20 (Full Moon)

- Chicago: 7:10 P.M.

- Fairbanks: 8:34 P.M.

Tuesday, September 21

- Chicago: 7:32 P.M.

- Fairbanks: 8:28 P.M.

Wednesday, September 22

- Chicago: 7:54 P.M.

- Fairbanks: 8:22 P.M.

Thursday, September 23

- Chicago: 8:16 P.M.

- Fairbanks: 8:16 P.M.

Friday, September 24

- Chicago: 8:41 P.M.

- Fairbanks: 8:10 P.M.

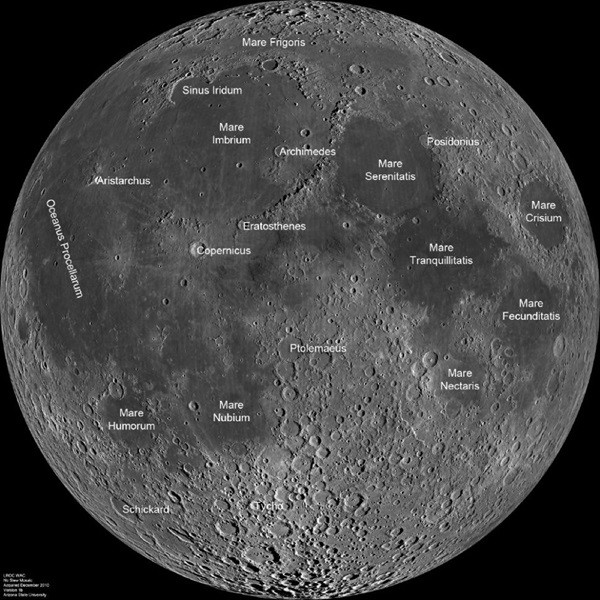

A slew of major lunar craters and maria are listed on this view of the Moon created using data from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

How to enjoy the Harvest Moon

The Full Moon is one of the easiest objects in the sky to observe. Because it rises around sunset, there’s no need to stay up late; alternatively, if you’re an early riser, it’s easy to catch just before sunrise. And, in fact, watching the Moon rise or set against any earthly backdrop gives you a chance to observe another effect, called the Moon illusion, which makes our satellite appear larger near the horizon than at zenith.

Researchers disagree on the exact reason this occurs; or perhaps it may differ from person to person, or depend on your observing conditions and location. Regardless of the reason, the illusion is most pronounced when the Moon is Full. And it is an illusion, the Moon isn’t changing apparent size over the course of a single night. However, the Moon does change apparent size as it goes from perigee to apogee — the closest and farthest points from Earth in its slightly elliptical orbit around our planet.

When the Moon is Full, its nearside (the only side we see from Earth) is on broad display. Most prominent are its large, circular maria, or seas. These weren’t ever filled with water but are instead ancient lava flows. They are also the youngest parts of the lunar surface and the regions NASA chose to send astronauts during its six manned Apollo landings. The Seas of Serenity, Tranquillity, Fertility, and Crises are the most prominent in the lunar east, which appears on our satellite’s right side when viewed from Earth’s Northern Hemisphere. In the lunar west, the Seas of Showers and Clouds, as well as the Ocean of Storms, loom largest. Tycho is perhaps the most prominent crater, spreading broad streaks, called rays, across the lunar south. Other noteworthy craters include, moving clockwise from Tycho, Byrgius (lunar southwest), Copernicus (lunar west), and Langrenus (lunar east).

Enjoying the Full Moon is an easy and fun activity for observers of all ages and experience levels. So, while the Harvest Moon is lighting the sky this week, make sure to enjoy the start of fall with a spectacular celestial show!

Source: Astronomy Magazine