Blog

The Sky This Week from March 15 to 24

Friday, March 15th 2019 07:19 PM

Friday, March 15The Big Dipper’s familiar shape rides high in the northeast on March evenings. The spring sky’s finest binocular double star marks the bend of the Dipper’s handle. Mizar shines at 2nd magnitude, some six times brighter than its 4th-magnitude companion, Alcor. Even though these two are not physically related, they make a fine sight through binoculars. (People with good eyesight often can split the pair without optical aid.) A small telescope reveals Mizar itself as double — and these components do orbit each other.Saturday, March 16Although asteroid 3 Juno reached opposition and peak visibility back in November, it remains a worthwhile target this week. Not only is it still reasonably bright — a small telescope will reveal its 9th-magnitude glow — but it also resides against the rich stellar backdrop of Orion the Hunter. This evening provides your best opportunity because the asteroid passes just 0.1° north of 5th-magnitude Pi1&n...

Read More

Read More

Scientists used IBM's quantum computer to reverse time, possibly breaking a law of physics.

Thursday, March 14th 2019 07:23 PM

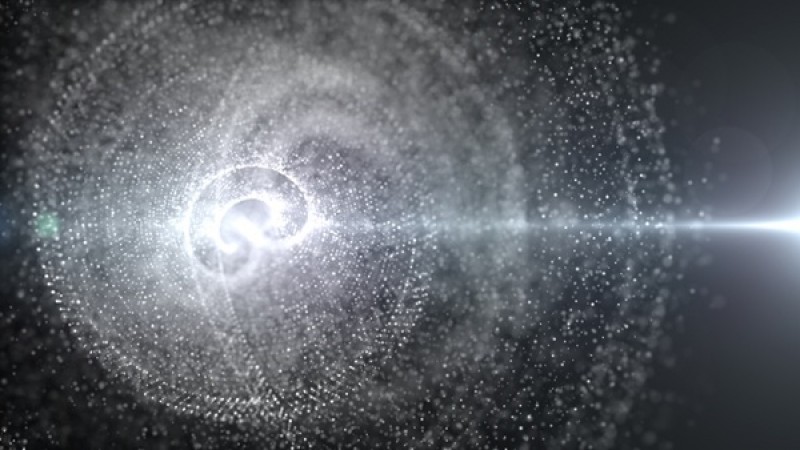

The universe is getting messy. Like a glass shattering to pieces or a single wave crashing onto the shore, the universe’s messiness can only move in one direction – toward more chaos and disorder. But scientists think that, at least for a single electron or the simplest quantum computer, they may be able to turn back time, and restore order to chaos. This doesn’t mean we’ll be visiting with dinosaurs or Napoleon any time soon, but for physicists, the idea that time can run backward at all is still a pretty big deal.

Normally, the universe’s trend toward disorder is a fundamental law: the second law of thermodynamics. It says more formally that any system can only move from more to less ordered, and that the chaos or disorder of a system – its entropy – can never decrease. But an international team of scientists led by researchers at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology think they may have discovered a loophole.

Computing p...

Read More

Read More

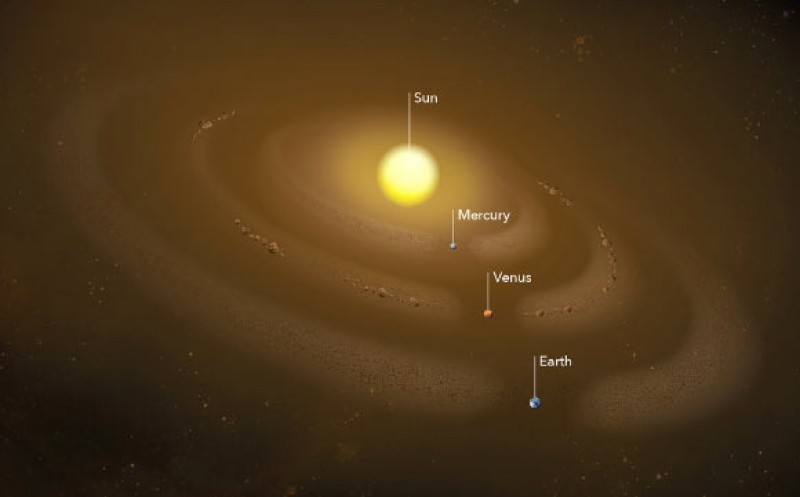

Astronomers Detect Circumsolar Dust Ring near Mercury’s Orbit

Wednesday, March 13th 2019 07:24 PM

“Scientists never considered that a dust ring might exist along Mercury’s orbit, which is maybe why it’s gone undetected until now,” said lead author Dr. Guillermo Stenborg, from the Space Science Division at the Naval Research Laboratory.

“They thought that Mercury, unlike Earth or Venus, is too small and too close to the Sun to capture a ring. They expected that the solar wind and magnetic forces from the Sun would blow any excess dust at Mercury’s orbit away.”

“We found it by chance,” he added.

Ironically, Dr. Stenborg and his colleagues, Dr. Russell Howard and Dr. Johnathan Stauffer, stumbled upon the dust ring while searching for evidence of a dust-free region close to the Sun.

At some distance from the Sun, according to a decades-old prediction, the star’s mighty heat should vaporize dust, sweeping clean an entire stretch of space. Knowing where this boundary is can tell scientists about the composition of the dust i...

Read More

Read More

NASA budget proposal funds Mars sample return, slashes other missions

Monday, March 11th 2019 09:52 PM

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine was at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Monday to talk about the proposed NASA budget for 2020.

While Bridenstine referred to the Trump administration’s proposed NASA budget as “strong,” and emphasized that funding for spaceflight exploration is high, the budget proposal also strikes funding from some missions. And, in total, it allocates $500 million less than what Congress appropriated for NASA last year.

Congress, not the executive branch, holds the power to set funding levels. The White House’s annual budget is a more of a policy statement about an administration’s desired approach. And with NASA budgets, Congress’s final funding levels often don’t reflect an administration’s proposals.

Budget Wins and Losses

This year’s proposal highlights NASA’s “Moon to Mars” program, providing funding for science missions on the lunar surface and for the...

Read More

Read More

Physicists suggest hunting 'Dark Matter Fossils' deep underground

Saturday, March 9th 2019 07:33 PM

In the elusive hunt for dark matter, some researchers are looking underground. The mysterious, unseen substance makes up more than 85 percent of the material in our universe. And since dark matter doesn’t interact much with normal matter (that’s what makes it “dark”), scientists usually rely on extremely large detectors to maximize their chances of observing a signal. But the physical hunt for dark matter is relatively new, so these experiments have only been running for a few years.

Now Stockholm University researcher Andrzej Drukier and his team say that there’s another way. They want to hunt for small rocks with evidence laid down over a billion years. In a new paper, published February 26 in the journal Physical Review D, Drukier’s team says that trading physical area for a massively longer timescale may make for an even more sensitive experiment.

Tiny signals

In many dark matter searches, researchers look for signals given...

Read More

Read More

It’s even harder to destroy asteroids than we thought

Friday, March 8th 2019 10:38 PM

You’ve likely heard by now that the movie Armageddon got it all wrong — it’s just not feasible to blow up an asteroid heading toward Earth with a bomb or few. But howunfeasible is it, really? New research set for publication March 15 in the planetary science journal Icarus is sending any hope humanity might have had to nuke an incoming asteroid threat even further into the realm of impossibility. Breaking up asteroids, it turns out, is really, really hard to do. The new study, led by recent Ph.D. graduate Charles El Mir from the Johns Hopkins University’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, makes use of both recent advancements in understanding about the way rock fractures, as well as improved computer code to model what happens when you smack an asteroid with something big. “Our question was, how much energy does it take to actually destroy an asteroid and break it into pieces?” El Mir said in a press release.The...

Read More

Read More

Planet-hunting ESO telescopes reveal Lagoon Nebula in all its glory

Monday, March 4th 2019 10:48 PM

The four 1-metre telescopes making up the European Southern Observatory’s new SPECULOOS planet-hunting array in Chile show off their near-infrared prowess with a spectacular look at a target familiar to countless amateur astronomers: the Lagoon Nebula, a vast cloud of gas and dust some 5,000 light years away in Sagittarius were stars and solar systems are in the process of forming.

As the name implies, SPECULOOS – the Search for habitable Planets EClipsing ULtra-cOOl Stars – is designed to study the nearest 1,000 faint, relatively cool stars and brown dwarfs, on the lookout for the tell-tale dimming that occurs when an orbiting planet moves in front of its host sun as viewed from Earth. By studying such light curves, astronomers can identify exoplanets in a star’s habitable zone where water – and thus, life as it’s known on Earth – could in theory exist. Exoplanets found by SPECULOOS and a twin observatory in the Canary Islands will...

Read More

Read More

March 2019: Spot the Winter Hexagon

Saturday, March 2nd 2019 10:31 PM

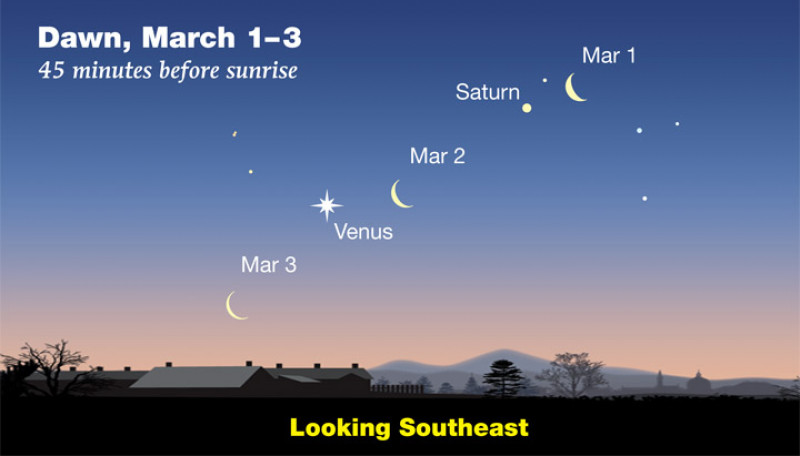

This month we’ll "clock" your interest in the switch to Daylight Time, cycle through the Moon's phases, check out three worlds at dawn, and focus on brilliant Sirius, the anchor star of the stunning Winter Hexagon. Read on!

March features two space-time events that have almost nothing to do with the starry sky itself but which definitely affect our enjoyment of it.

First, on March 20th at 5:58 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time, Earth reaches one of the two equinox points in its year-long orbit. But there's more to it than just "the beginning of northern spring, astronomically speaking." Equinox comes from the Latin word aequinoctium, meaning "equal nights." On this date, days and nights everywhere are both 12 hours long. And on the equinox, the Sun rises due east and sets due west no matter where you are.

Second, March is when billions of clocks "spring forward" in a shift to Daylight Savings time. But the date for all that time-shifting varies: It comes on March...

Read More

Read More

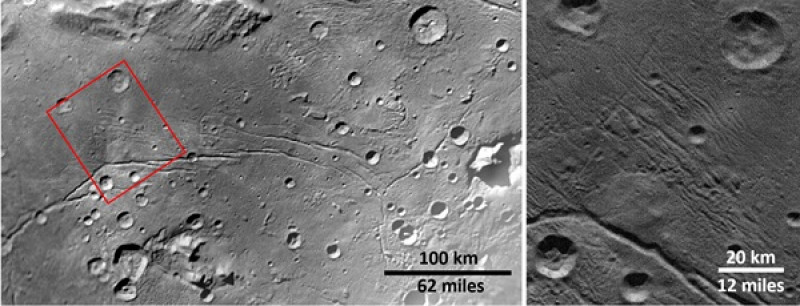

Craters on Pluto and Charon show Kuiper Belt lacks small bodies 228 Craters on Pluto and Charon show Kuiper Belt lacks small bodies

Friday, March 1st 2019 08:39 PM

Home

/

News

/

Craters on Pluto and Charon show Kuiper Belt lacks small bodies

228

Craters on Pluto and Charon show Kuiper Belt lacks small bodies

Of all the scars on these distant worlds, none are small, challenging astronomers' beliefs about the types of objects that orbit far from the Sun.

By Korey Haynes | Published: Thursday, February 28, 2019

Craters on Pluto and Charon only get so small, pointing to new information about the Kuiper Belt.

NASA/JHU-APL/SWRI/K. Singer

When New Horizons flew past Pluto and its moon Charon in 2015, it took a lot of pictures. From studying those images, scientists have recently realized that while both bodies are covered in craters, almost none of those craters are small, meaning there may not be many small bodies around to smash into them. This changes astronomers’ views of the Kuiper Belt, the region of small – but apparently not too small – rocky and...

Read More

Read More

Merging galaxies can cause a dearth of new stars

Thursday, February 28th 2019 11:59 PM

Galactic smash-ups can reignite or destroy galaxies — but which will it be? Astronomers using space- and ground-based telescopes to peer inside the mergers of nearby galaxies are hoping to learn more about these events and what they mean for the history and future of our universe.

Mergers: Good or bad?

Galaxy mergers have built our universe into the place it is today. Over time, smaller galaxies crash into each other, creating larger, more complex structures. But what exactly happens during a merger — and what it will wreak on the resulting larger galaxy — is a difficult question to answer. The result even seems to differ from merger to merger. While some mergers ignite star formation, lighting up the resultant galaxy in a starburst, others appear to quench it, effectively killing the galaxies much faster than if the merger had never occurred. Most mergers in the universe were taking place about 6 billion to 10 billion years ago. That means they are far away...

Read More

Read More